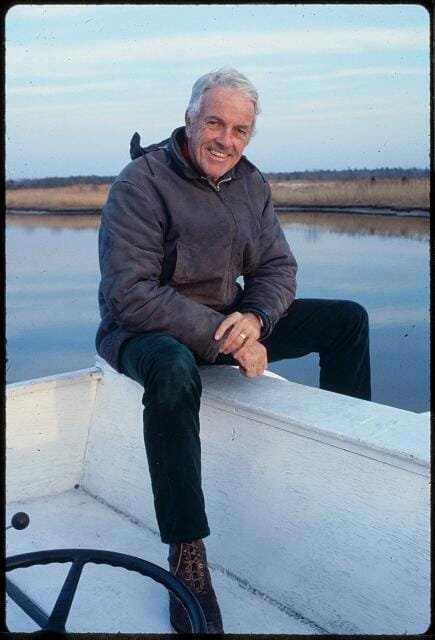

The title maverick in political terms rarely is reserved for elected officials. To be bestowed with this title, the elected official must demonstrate an independent mind, which involves putting the needs of one’s country before political party allegiance. Last August 31 was former first congressional district congressman Otis Pike’s 100th birthday. He earned this title.

Born in Riverhead on August 31, 1921, Otis Grey Pike endured hardships from a young age. His parents died at when he was only six years old. His oldest sister raised him. From economic instability and bearing witness to the struggles of the average working-class person during the Great Depression, Pike pulled himself out of poverty and got involved in town politics as a Franklin Roosevelt-inspired Democrat. Following his service as a fighter pilot in World War II, Pike graduated from Colombia University with a law degree. Building on his shared experiences with other demobilizing troops, Pike set his political aspirations on the First Congressional District seat long-held by Stuyvesant Wainwright.

In contrast to Pike, Wainwright was the son of an heiress to a railroad fortune. Raised on the narrative of a wealthy elite, Wainwright was locked in a battle with Robert Moses over the preservation of Fire Island. Moses proposed closing the Fire Island Inlet in his reclamation project. The inlet was one of the first planned projects which would eventually lead up to Moses’s goal of constructing a four-lane highway through Fire Island. Wainwright, in opposition, aggressively opposed the closing of the inlet and demanded the complete restoration of it. He argued that the inlet was fundamental for shipping oil, building material, and a possible local evacuation route necessary for civil defense.

But hurting his image and argument was another point he made on the economic impacts of East End Yachts’ inconvenienced leisure activities. Furthering the confrontation with Moses, Wainwright was exploring the possibility of creating a National Park on Fire Island, which would have conflicted with any plans Moses had for a four-lane extension of Ocean Parkway on Fire Island. Moses quickly used his classic argument that the “privileges of a few should not outweigh the benefits of many.” Newsday cemented Wainwright’s argument as elitist, with headlines that read, “The myth that Long Island is a playland of exclusive beaches and polo fields for fun-loving millionaires will plague Representative Stuyvesant Wainwright.”

In 1960, ceasing on the opportunity to defeat Wainwright, Pike used the Moses fight to his advantage. Being distracted by the ongoing feud with Moses and the media portraying Wainwright as Long Island’s wealthy and out-of-touch elite, Pike modeled himself as the average person’s candidate. Extending an olive branch to Moses, Pike publicly stated, “Wainwright’s feud with Moses has not accomplished any preservation of Fire Island or any constructive erosion programs.”

Wainwright did not respond to Pike’s criticism, but further dug into the feud with Moses by stating, “Moses secretly approved a plan to build a $10,000,000 bridge that would link Captree State Park to Fire Island.”

Publicly disclosing the backroom deals of Moses and rumors of his plan for a four-lane parkway traversing Fire Island coming out did little to boost Wainwright’s image. Moses’s damaging attacks labeling Wainwright an elitist, would secure Pike’s election win in 1960. Despite winning on the coattails of Moses and Wainwright’s war of words, Moses would be surprised to learn Pike was independent-minded and would not be swayed by any state power broker.

Later in his career, Pike was asked to describe his district. Pike summed up his answer by replying, “I’m surrounded on three sides by water and the fourth side by Republicans.”

Pike being a Democrat in a sizable Republican district would have him develop the skill of being independently aligned on much of his policy. His first test was the newly exposed plans for constructing the Fire Island Parkway. Under the threat of bulldozers, 17 communities across Fire Island unified to oppose the construction of any parkway. Dunewood homeowner and property developer Maurice Barbash and his brother-in-law Irving Like built a grassroots campaign with solid support from mainland Long Islanders to preserve Fire Island. Pike witnessing the growing movement for preservation and refusing to pledge any support to Moses, joined the opposition, which evolved into designating Fire Island a National Seashore.

Following the success of Fire Island becoming a National Seashore, Pike would navigate his 18 years as a congressman by supporting issues not exclusive to any political party. Pike’s political reelection advertisements would embrace his independent stance by stating, “Don’t vote for the coat. Pike’s opponents have run on the coattails of others, but Pike has run on his two legs and stood upon them for us.”

Towards the end of his tenure in 1975, Pike would investigate the role of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in coups and spy operations on American citizens. His committee hearing, investigation, and demands for more oversight in the CIA were voted and passed by the house to remain secret. In response, the so-called Pike Report was leaked to the Village Voice newspaper by Pike himself. In 1979 Pike left politics to become a news columnist. He stayed in his second career until his death in 2014 at 92 years old. The bygone value of putting the needs of one’s country before political party allegiance also died that January day.