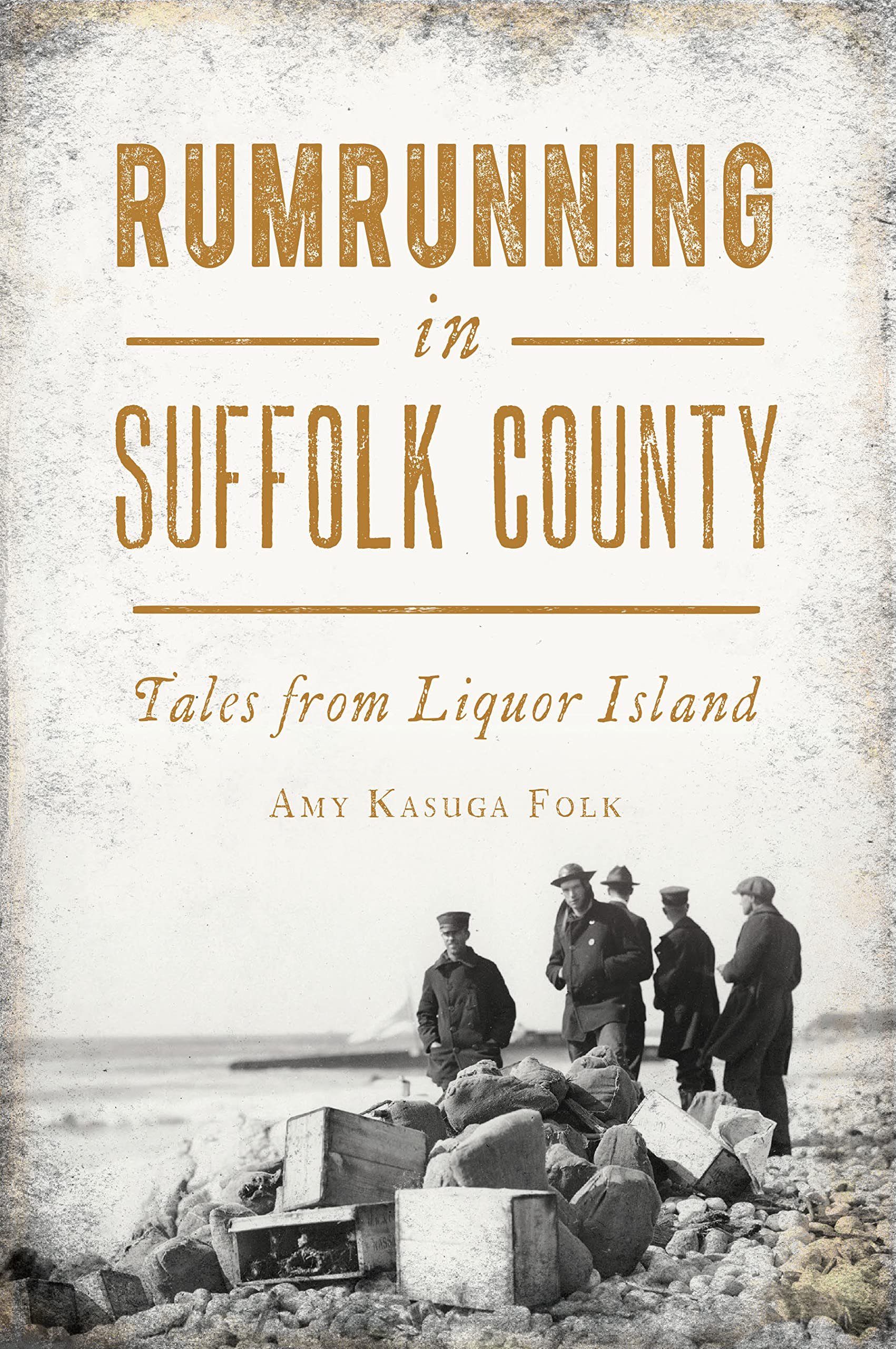

“Rumrunning in Suffolk County: Tales from Liquor Island”

By Amy Kasuga Folk

Non Fiction

Fix yourself a little drinky-poo – or a big one (it’s legal) – and pour over the pages (figuratively of course) of Amy Kasuga Folk’s “Rumrunning in Suffolk County:Tales from Liquor Island.” It’s a-brim with stories and accounts on how back in the day, Long Island earned the nom de plume of “Liquor Island.”

Booze, grog, hooch and John Barleycorn are just a few tags for the drink that was nationally banned from 1920-1933. Also known as the “noble experiment,” Prohibition was our government’s lofty attempt to reduce crime and corruption, solve social problems, and improve health and hygiene in America. Prohibition achieved none of the above. If anything, it created more crime (bootlegging and rumrunning), solved no social problems and worsened the health of our country’s citizens (menthol poisoning from the homemade stuff).

Folk describes how Long Island’s proximity to its coastal communities and big distribution markets such as New York City, made it a dream spot for distributing the illegal brew. Shipments came from as far as Europe, others as nearby as New Jersey, while local vessels moved out to meet them and collected the contraband.

Townsfolk, especially those with shoreline houses, unwittingly became part of the criminal operation. Discovering that cases of booze awaiting further transit had been stashed in their garages (borrowed for the night), homeowners found a bottle or two of hootch left by the smugglers as a thank you. Fearful of what would happen if they reported the goings on (the bootleggers were a violent lot) the community turned a blind eye. Though on occasion, someone did brave it and reported the crime.

Such a one was Annie L. Fuhrmann of Greenport. Fed up with her husband’s rumrunning and drinking away his pay she decided to go his bosses and ask for half his salary to live on. They “only laughed and said it was my funeral. Well, I want to make it their funeral too.” It’s not nice to laugh at Annie Fuhrmann.

After starting out as an informant, she was later hired as an investigator and had the satisfaction of wrecking the rumrunning ring and sending its leader to jail. The bad news: her drink-loving husband turned up six months later with a bullet in his head. “The murderer was never found.”

Folk cites this era as the start of organized crime in the U.S., the early stages of groups that would morph into versions of the mafia. Racketeers used the new wireless technology to send messages and secret codes placing orders, arranging drop-offs, and warn of a possible bust by the feds.

A code book used by the criminals was discovered by fisherman Samuel W. Boerum. Talk about a catch! Afraid that if he turned it in and word got out, he’d be at mercy of a vengeful gang, yet realizing it was valuable, Boerum “dried the book out and hid it away.” Alphabetized, the work contained the codes for everything from “Are you sure?” to “When can you be there?” Passed down to his grandson, Donald H. Boerum, “a passionate local historian,” the artifact remains with the Oysterponds Historical Society as a symbol of the Prohibition era.

Profiteering from Prohibition were the likes of Lucky Luciano and Dutch Schultz, names that ring a bell and would ring a neck at the drop of a drop of scotch. They and their ilk netted millions at a time when 35 cents bought a pound of coffee.

The demand for alcohol and the means to get it from place to place was so strong in 1927, that cars were taken from homes, from businesses and from parking lots across Long Island. Days later they were found in the city, mileage galore topping off their speedometers. The police put the thefts onto rumrunners. “Citizens were advised to start locking their car doors.”

Photos from the Library of Congress and other sources show police in hats and badges. In A New Packard Eight ad, the note below tells how bootleggers favored the large boxy touring cars “to transport their haul up the island,” adding to the climate of the 1920s and 1930s.

Car chases and shootouts; bar, farm and loading party raids; powerful gangs dodging the U.S. Coast Guard in speedboats – these tales have a cops and robbers feel to them and make for an exciting read.

Whew! After all that I think it’s time for another drinky-poo. Mixologist, hit me again! And make it a double this time.