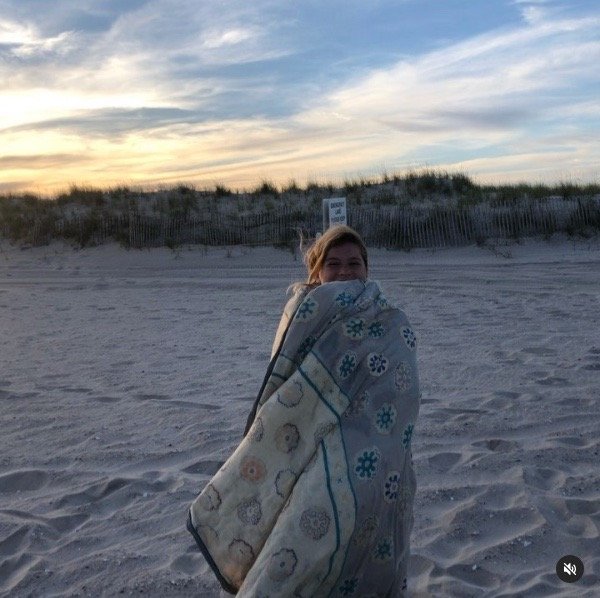

I fell asleep surrounded by the four walls of my college apartment bedroom on Geneseo’s Main Street after another week of blankly staring at a rotation of my four professors on Zoom. What made my nap on Feb. 27 extraordinary though, were the three missed calls from the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) that welcomed me back to reality.I learned from my very hesitant call back to the state that those same four walls now barricaded me from the outside world because my 21-year-old body became infected with COVID-19.There was a very obvious slew of questions, relative to my own basic survival in a state of panic, that caused those four walls to close in on me: How am I going to get food? Will I even be able to taste it? Do I have medicine? How am I going to get my work done if I start to feel sick? How can I possibly manage social isolation for an entire two weeks?I confronted the answers to these questions in the coming days and managed them as they arose, some with more obvious obstacles than others. My two weeks in isolation cost a few hundred dollars of Instacart orders, a dozen missed assignments that I’d spend the following weeks dazed over, a state of lethargy like no other, and a social deprivation that felt like it would never end.Thankfully, I was able to taste the dramatic amount of food that I ordered to keep myself occupied, but I didn’t have the energy to cook it. The first two days I tried my hardest to maintain positivity and motivate myself to view my time in isolation as a period of self-care. I aimed to get ahead on work, maybe experiment with a few recipes, and virtually catch-up with my loved ones.None of these things happened over those two days. On the third morning, I woke up with swollen glands and congestion that replicated an awful strep throat. Unfortunately, it only got worse, which prompted more Instacart orders of soup, medicine, and tissues.I did what any college student would do: I called my mother with the little scratchy voice I had left and begged for help, but she was able to offer none. I was infected with a virus that could pose deadly consequences for her and I was seven hours from home. I was alone in uncharted territory.I woke up almost every morning at around 2 a.m., covered in a summer-night’s sweat, to find snow piled on the ground outside of my window. I would grab my phone to discover even more missed calls from the NYSDOH. My only social interactions were limited to my telecommunications with a representative assigned to monitor my symptoms, to which they were only getting worse.I was confined to my lofted, surrounded by four fans, one at every corner. My movement throughout my isolation was limited to alerting Netflix with a click to the remote that yes, “I’m still watching,” microwaving soup, emailing my professors that I wouldn’t be able to attend class, and turning the fans on and off to match my fluctuating fever.On the sixth day, I woke up with terrible back pain, prompting yet another Google search, “is back pain a symptom of COVID-19?” It was then I learned that every feeling and symptom imaginable could be related to the virus, which is something I thought I understood, until it all crashed on top of me at once.I had absolutely no motivation to do anything but watch TV and scroll through the same six apps on my phone for the first nine days, until finally on the 10th, I had an appetite for anything but soup, and an impulse for any activity far from my phone, laptop or television.That day, I tried to read a book for class since I was feeling better. After about two pages, I realized that I was retaining none of what I was reading. This is the moment where I learned that “COVID brain” was not just a figment of my imagination. It was overwhelmingly difficult to try and do anything academic.When I spoke to the NYSDOH that day, I asked if I was allowed to walk around outside with a mask on, remaining in a socially distant proximity to others. The representative had told me yes, but I remembered an email from my college with a set of guidelines that said no. When I mentioned this, she said, “Well, listen to them then.”There seemed to be no real consensus on what exactly was safe and what wasn’t between the NYSDOH and my college. There were completely different sets of guidelines that made the entire experience daunting to navigate correctly. Scared of the potential consequences going on a walk could pose, I stuck my head out of my window from time to time just to feel as if I was breathing new air.I spent the next few days in better health making a list of all the work that I had missed. The overwhelming checklist sent me into a 12-hour sleep. There seemed to be nothing to do except sleep. In my period of isolation, I was never tired, but I was always sleeping.On the final 12th day, I was released from isolation. Walking to go see my friends was a commodity I came to realize was a privilege … even walking around outside felt like a privilege. As I looked up at my bedroom window on the storefront my apartment sits on, the imaginary image of me sticking my head out my bedroom window made me sick to my stomach.On the 14th day, I found a missed call attached to a voicemail from my College health center alerting me that on March 15, I would be released from quarantine. I had been out of quarantine for two days as mandated by the state, but at least there was humor to be found in the disconnect at that point.Approaching six months from my experience with COVID-19 as a college student, I can’t help but reflect upon where we now stand with the virus as both an American and a New Yorker.When I was infected myself, things were much different than they are now. When the virus first reached the U.S., I found myself driving up and down Ocean Parkway everyday out of boredom. The days blended into one another and it became difficult to differentiate a Friday from a Monday.On one particular Monday though, as I went to unlock my car parked in front of my family’s Bay Shoe home, my mother chased me outside in her pajamas with tears in her eyes. It was then I knew that my grandmother’s boyfriend of nine years, who I considered a grandfather, had lost his life to the virus.He traveled to the hospital only a week earlier for a minor medical condition and had contracted the virus while spending only two hours in the hospital. What would two months earlier had been a routine trip to the hospital had cost him his life.My family and I then spent everyday like many other New Yorkers, watching Governor Cuomo on the television, crossing our fingers that he’d soon announce that a vaccine had been developed.As soon as the announcement finally came, I got my vaccination against COVID-19 without any hesitation. I got the vaccine not only because I’d like to avoid having to relive the experience I’d had in my college apartment, but because I don’t want my family members to die … or anyone else.It sounds harsh, but the reality is that the pandemic has been. As a woman turning 22-years old, I won’t die from the virus, but I possess the ability to contribute to the deaths of others by not getting vaccinated. And that wasn’t a risk I was willing to take living with my 88-year-old grandmother.Only a few months ago as Americans, we listened to President Biden say that the worst of the pandemic was behind us. We listened to Governor Cuomo say he was ordering the closure of the largest vaccination sites in the state, Jones Beach included. Many people, myself included, were lulled into believing that we were entering a “post pandemic” world.Yet, only three weeks after Biden’s announcement, the highly contagious Delta variant skyrocketed infections beyond where we’d stood as a nation last summer. Yet many people are fighting for their unvaccinated children to be maskless in schools across the island, and the county.While having to wear your mask is restricting, I remind those reading and myself everyday that taking the precautions to protect yourself from the virus are not just for you, but for your loved ones and communities at large. The loss of a loved one or watching those you love suffering can be devastating, but having to wear a mask in school is just objectively far from it.

I fell asleep surrounded by the four walls of my college apartment bedroom on Geneseo’s Main Street after another week of blankly staring at a rotation of my four professors on Zoom. What made my nap on Feb. 27 extraordinary though, were the three missed calls from the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) that welcomed me back to reality.I learned from my very hesitant call back to the state that those same four walls now barricaded me from the outside world because my 21-year-old body became infected with COVID-19.There was a very obvious slew of questions, relative to my own basic survival in a state of panic, that caused those four walls to close in on me: How am I going to get food? Will I even be able to taste it? Do I have medicine? How am I going to get my work done if I start to feel sick? How can I possibly manage social isolation for an entire two weeks?I confronted the answers to these questions in the coming days and managed them as they arose, some with more obvious obstacles than others. My two weeks in isolation cost a few hundred dollars of Instacart orders, a dozen missed assignments that I’d spend the following weeks dazed over, a state of lethargy like no other, and a social deprivation that felt like it would never end.Thankfully, I was able to taste the dramatic amount of food that I ordered to keep myself occupied, but I didn’t have the energy to cook it. The first two days I tried my hardest to maintain positivity and motivate myself to view my time in isolation as a period of self-care. I aimed to get ahead on work, maybe experiment with a few recipes, and virtually catch-up with my loved ones.None of these things happened over those two days. On the third morning, I woke up with swollen glands and congestion that replicated an awful strep throat. Unfortunately, it only got worse, which prompted more Instacart orders of soup, medicine, and tissues.I did what any college student would do: I called my mother with the little scratchy voice I had left and begged for help, but she was able to offer none. I was infected with a virus that could pose deadly consequences for her and I was seven hours from home. I was alone in uncharted territory.I woke up almost every morning at around 2 a.m., covered in a summer-night’s sweat, to find snow piled on the ground outside of my window. I would grab my phone to discover even more missed calls from the NYSDOH. My only social interactions were limited to my telecommunications with a representative assigned to monitor my symptoms, to which they were only getting worse.I was confined to my lofted, surrounded by four fans, one at every corner. My movement throughout my isolation was limited to alerting Netflix with a click to the remote that yes, “I’m still watching,” microwaving soup, emailing my professors that I wouldn’t be able to attend class, and turning the fans on and off to match my fluctuating fever.On the sixth day, I woke up with terrible back pain, prompting yet another Google search, “is back pain a symptom of COVID-19?” It was then I learned that every feeling and symptom imaginable could be related to the virus, which is something I thought I understood, until it all crashed on top of me at once.I had absolutely no motivation to do anything but watch TV and scroll through the same six apps on my phone for the first nine days, until finally on the 10th, I had an appetite for anything but soup, and an impulse for any activity far from my phone, laptop or television.That day, I tried to read a book for class since I was feeling better. After about two pages, I realized that I was retaining none of what I was reading. This is the moment where I learned that “COVID brain” was not just a figment of my imagination. It was overwhelmingly difficult to try and do anything academic.When I spoke to the NYSDOH that day, I asked if I was allowed to walk around outside with a mask on, remaining in a socially distant proximity to others. The representative had told me yes, but I remembered an email from my college with a set of guidelines that said no. When I mentioned this, she said, “Well, listen to them then.”There seemed to be no real consensus on what exactly was safe and what wasn’t between the NYSDOH and my college. There were completely different sets of guidelines that made the entire experience daunting to navigate correctly. Scared of the potential consequences going on a walk could pose, I stuck my head out of my window from time to time just to feel as if I was breathing new air.I spent the next few days in better health making a list of all the work that I had missed. The overwhelming checklist sent me into a 12-hour sleep. There seemed to be nothing to do except sleep. In my period of isolation, I was never tired, but I was always sleeping.On the final 12th day, I was released from isolation. Walking to go see my friends was a commodity I came to realize was a privilege … even walking around outside felt like a privilege. As I looked up at my bedroom window on the storefront my apartment sits on, the imaginary image of me sticking my head out my bedroom window made me sick to my stomach.On the 14th day, I found a missed call attached to a voicemail from my College health center alerting me that on March 15, I would be released from quarantine. I had been out of quarantine for two days as mandated by the state, but at least there was humor to be found in the disconnect at that point.Approaching six months from my experience with COVID-19 as a college student, I can’t help but reflect upon where we now stand with the virus as both an American and a New Yorker.When I was infected myself, things were much different than they are now. When the virus first reached the U.S., I found myself driving up and down Ocean Parkway everyday out of boredom. The days blended into one another and it became difficult to differentiate a Friday from a Monday.On one particular Monday though, as I went to unlock my car parked in front of my family’s Bay Shoe home, my mother chased me outside in her pajamas with tears in her eyes. It was then I knew that my grandmother’s boyfriend of nine years, who I considered a grandfather, had lost his life to the virus.He traveled to the hospital only a week earlier for a minor medical condition and had contracted the virus while spending only two hours in the hospital. What would two months earlier had been a routine trip to the hospital had cost him his life.My family and I then spent everyday like many other New Yorkers, watching Governor Cuomo on the television, crossing our fingers that he’d soon announce that a vaccine had been developed.As soon as the announcement finally came, I got my vaccination against COVID-19 without any hesitation. I got the vaccine not only because I’d like to avoid having to relive the experience I’d had in my college apartment, but because I don’t want my family members to die … or anyone else.It sounds harsh, but the reality is that the pandemic has been. As a woman turning 22-years old, I won’t die from the virus, but I possess the ability to contribute to the deaths of others by not getting vaccinated. And that wasn’t a risk I was willing to take living with my 88-year-old grandmother.Only a few months ago as Americans, we listened to President Biden say that the worst of the pandemic was behind us. We listened to Governor Cuomo say he was ordering the closure of the largest vaccination sites in the state, Jones Beach included. Many people, myself included, were lulled into believing that we were entering a “post pandemic” world.Yet, only three weeks after Biden’s announcement, the highly contagious Delta variant skyrocketed infections beyond where we’d stood as a nation last summer. Yet many people are fighting for their unvaccinated children to be maskless in schools across the island, and the county.While having to wear your mask is restricting, I remind those reading and myself everyday that taking the precautions to protect yourself from the virus are not just for you, but for your loved ones and communities at large. The loss of a loved one or watching those you love suffering can be devastating, but having to wear a mask in school is just objectively far from it.