Besides the obvious — beaches, beauty, and solitude — a major reason Fire Island is so popular is its proximity to New York City and its environs, drawing on a population of 12 million people within a 50-mile radius. Its draw is also the ease of access for those who choose Fire Island for their getaway, the ability to get there in reasonable amounts of time with as little hassle as possible. The Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) and the various ferries that leave from the few strategic communities along Long Island’s south shore provide this access.

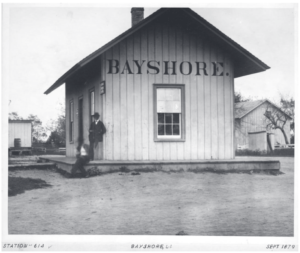

The LIRR local from Penn Station in Manhattan to Bay Shore/Sayville ordinarily takes about 90 minutes. An express train can take as little as 70 minutes. Then a short jaunt by jitney to the ferry terminal, a usually beautiful, mind clearing half-hour boat ride to the island and you are in a new world.

Access has always been a top priority, even early on in Fire Island history.

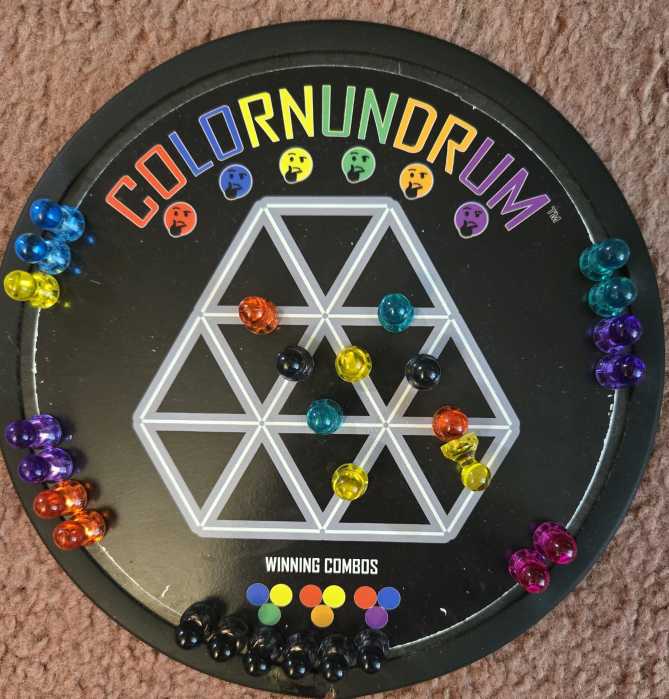

Back in 1855 David Sammis purchased 120 acres east of the Fire Island Lighthouse and erected the world famous Surf Hotel. At its peak, the hotel accommodated 1,500 guests and, with gas lamps and telegraph, it took its place among the top most celebrated resorts on the Atlantic coast.

But Sammis had to get his guests to the island. He built his own trolley line from the Babylon train station to the dock where his personal steam yacht carried them to Fire Island, a trip that took, in total, not much more than two hours.

And even that would not have been possible without the LIRR.

The history of America’s railroad industry follows that of most startup businesses. In 1826, the railways established themselves as the transportation fix for the future, albeit mostly covering only short distances, often using different gauge track. As the industry expanded, inefficient lines were consolidated within larger companies, until 1906 when seven entities, owned by men like J.P. Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Jay Gould, controlled two-thirds of the country’s railroads. One of these was the Pennsylvania Rail Road (PRR), which became, for a time, the largest corporation in the world with a budget in excess of that of the U.S. government. The corporation paid out dividends for over a hundred years, a record that remains unbroken to this day. In 1906 the PRR absorbed the LIRR.

One of America’s first major railways was the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O). It used horses to pull the train cars until the advent of steam in 1829. The first American locomotive was called the “Tom Thumb,” a coal-fired, vertical boiler steam engine whose tubes were rifle barrels. In a race between a horse and the locomotive, the horse won when “Tom Thumb” broke down. Even so, steam was here to stay.

The original, and rather audacious, LIRR plan was for a rail line that would provide daily commuter service from Brooklyn all the way to Boston with a steamship connection from Greenport on Long Island’s North Fork to Stonington, Connecticut, where passengers would pick up the Boston-Providence Rail Road for the final leg into Boston. The estimated time for this trip was 11 hours – not bad for 1834. Before this endeavor could be completed, however, the New York, New Haven and Hartford rail line was built over “impassable” southern Connecticut to provide service from New York to Providence and eventually Boston, negating its need.

One of the first lengths of track built on Long Island was for the Brooklyn and Jamaica Rail Road (B&J), a 10-mile stretch from the East River to Jamaica. It was immediately subsumed by the LIRR to complement its line originating in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The main line continued to be Brooklyn to Greenport, its first run completed in July 1844, a journey that took only three and a half hours. Today’s schedule allots three hours and five minutes for the same trip.

Meanwhile, additional branches were being built by various entrepreneurs trying to carve out market niches for themselves. One line reached Hicksville in1837, Hempstead in 1839, Deer Park in 1841 and Millville (Yaphank) in 1844. Nearby residents in Huntington and Babylon had to take stagecoaches (today’s taxis) to these stations.

One of these competitors was known as the South Side Railway, consolidated in 1860, authorized to run along the south shore of Long Island as far as Islip. In 1867 its charter was extended out to East Hampton. Regular service to Seaside (Babylon) began in October of 1867 and to Patchogue in April of 1869, but often had to rely on other railroads (Brooklyn Central for one) and/or horse cars to complete the trip.

The line pushed its way further east, establishing a Sag Harbor Branch, now called the Montauk Branch. It opened in 1869, running from St. George’s Manor (Manorville) to Hampton Bays, extending to Sag Harbor and Bridgehampton in 1870, and finally Montauk in 1895.

The hamlet of Manorville was once part of a land grant given to Col. William “Tangier” Smith in 1693 for his service as governor of Tangiers, Morocco. Called the Manor Saint George, it was an enormous tract of land, reaching from present day Mastic all the way to Southampton, from the Atlantic Ocean in the south, to Route 25 (Calverton) in the north, including some 50 miles of barrier beach — including Fire Island.

The Long Island Rail Road in competition with the South Side Railway ran its tracks into Manorville in 1844, to a station then called Manor St. George. The station agent, a revolutionary war patriot named Seth Raynor, was so incensed at the reference to St. George, the patron saint of England and its monarchy (so the story goes) that when his wife was painting their fence, Seth grabbed a brush and painted over the words “St. George” leaving the name of the station as “Manor.” It stuck, becoming Manor Station in 1852, and with the opening of the post office in 1907, officially as Manorville.

Finally, in 1875-76 a wealthy rubber baron, and owner of the Flushing and North Side Rail Road, named Conrad Poppenhusen, acquired all the railroads on Long Island and consolidated them into the network we now recognize as the LIRR.

On Nov. 8, 1867, an article in the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper described the opening of the South Side Railway in part, as follows: “The South Side Railroad which has been pushed forward with commendable energy is now open for travel from Jamaica to Sayville, a distance of forty-one miles. By this road a productive section of Long Island is brought within easy access of Brooklyn and New York, adding millions to the value of the property on the Island and in this city, if we are not blinder than bats to our own interests …

The newspaper goes on to describe, if not so rhapsodically, the various stations along its route with such foreign names as Pearsall’s Corner (Lynbrook), “within five miles of the popular bathing resort of Far Rockaway,” Baldwinville, Seaside (Babylon), and Penaticutt/Penataquit (Bay Shore).

The paper continues, in no uncertain terms, that its interest is really in the benefits this new railway system would provide Brooklyn.

“The folly of diverting the trade of Long Island is so apparent that it can hardly be necessary to waste words or space upon it. Those who come after us will find it hard to believe for ever [sic] a generation, after steam has been introduced, we saw the produce of the island carted by our very doors, while we were content to follow it to New York, and purchase it when it had lost its freshness, and after three or four classes of hucksters had made a profit upon it … In the kitchen is embraced an important department of domestic economy, and no man who is not a candidate for the lunatic asylum, would provide pictures of his parlor while destitute of the means of properly cooking a beef-steak below stairs.” (The place where the servants lived and worked – possibly the basement.)

And the paper was not done. The column goes on to extol the pleasures that await their readers brought on by this new railway.

“The summer travel upon it can hardly fail in being immense for the road will connect with many of the most popular bathing and fishing resorts on the south side of the island. Passengers to Rockaway, by taking the cars to Pearsall’s Corner (Lynbrook), will have an easy stage ride of less than five miles.”

We now have our own 375 horsepower, taxi (stagecoach) rides from the LIRR to the ferries servicing Fire Island.

The Long Island Rail Road, chartered in 1834, is the second oldest (after the Strasburg Rail Road in Pennsylvania) U.S. railroad still operating under its original name. It provides service 24/7, year-round, transporting nearly 350,000 passengers every weekday making it the busiest commuter railroad in North America.

LIRR trains may run late occasionally and may not always be as clean as we might like, but a well deserved thank you should be nodded in the direction of those who made possible such easy access to our sliver of paradise.

This article was originally published under the title “Long Island Rail Road’s History with Fire Island” on pages 44 and 45 in the print edition Fire Island News on July 7, 2017.