Gunpowder and Gumption

By Thomas McGann

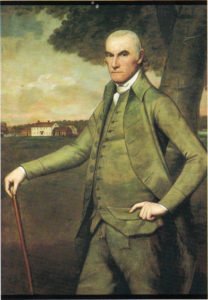

This year celebrates the 300th anniversary of the William Floyd Estate, one of the gems of the Fire Island National Seashore. The estate is the ancestral home of William Floyd (1734-1821), one of only 56 original signers of the Declaration of Independence.

The estate is not contiguous with the rest of the FI National Seashore. It sits on 613 acres of forest, fields and marsh land approximately two miles south of Sunrise Highway in Mastic Beach, fronting both Narrow and Moriches bays. It contains the Old Mastic House, and 12 out buildings reflecting three centuries of American life.

The estate has an interesting, if somewhat convoluted, history.

The English born William “Tangier” Smith (1655-1705) who had been mayor of Tangier, Morocco (hence his nickname), was granted patents (land grants) in America in recognition of his service to the Crown. He added extensive purchases of various Indian lands until by 1697, he had accumulated more than 81,000 acres, stretching from the Southampton Town line to Shirley, from Route 25 in the north to the Atlantic Ocean in the south, including 24 miles of Great South Barrier Beach now known as Fire Island.

In 1718, Richard Floyd, William Floyd’s great-grandfather, emigrated from Wales to America where he purchased 4,400 acres from the Tangier Smith family. That acreage included all the “beach, meadow, and bay” stretching six miles north from Moriches Bay to one mile west of the Forge River. He also acquired the Fire Island tract.Both families built homes – a mere three miles apart. With the death of William Tangier Smith his property was divided between his sons. His Setauket estate, being considered the more valuable, was inherited by his oldest son, while the Mastic property was left to the second oldest. The Manor of St. George was completed on the Mastic property about 1709.

Meanwhile, in 1724 Nicoll Floyd inherited property from his father Richard and proceeded to build the first portion of the Old Mastic House, a six-room, two-story, wood frame home. Nicoll Floyd established a successful plantation, expanding the home as his wealth and family grew. Upon his death in 1755, he left the property to his oldest son, William Floyd, signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Floyd married twice. He had three children with his first wife Hannah Jones, who died in 1781, and two children with his second wife, Joanna Strong. Mary Floyd, William Floyd’s eldest daughter, married Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge in the Old Mastic House. Tallmadge would later play a major role in the fate of the Manor of St. George.

William Floyd became active in politics, becoming a delegate in both the First and Second Continental Congresses. In the Old Mastic House he hosted the likes of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and the Marquis de Lafayette.

But Americans were chaffing under the yoke of British policies – particularly taxation without representation. Sparked by the Stamp Act in 1765, followed by the Boston Massacre, and the battle of Lexington and Concord, the Founding Fathers first drafted and then signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

However New York members of the Continental Congress were in a predicament when it came to signing this historic document. Floyd and his fellow delegates could not vote on the matter of independence until they received formal authorization from New York’s home assembly to do so. Without it, all they could do was standby and wait. Said authorization arrived later that summer, and Floyd was the first of the New York delegates to place his signature upon being given the green light to act.

These days we celebrate the signing of the Declaration of Independence by going to the beach, and ballgames, and backyard barbecues with scarcely a thought of how momentous that act really was. Only 56 men signed the document, and by doing so they were guilty of treason, putting their lives on the line. That’s a lot of gumption, guts and grit.

Later, Benjamin Franklin is quoted as having said, “We must, indeed, all hang together or, most assuredly we shall all hang separately.” But the last sentence of the Declaration of Independence says it best. “And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.”

Let that sink in for a moment – or two.During the Revolutionary War both the Old Mastic House and the Manor of St. George were occupied by British military forces. William Floyd’s estate was occupied by a company of horsemen for the remainder of the war, and he and his family were forced to flee to Connecticut.

Judge William Smith III took his family to Kingston, New York, after the British garrisoned the Manor of St. George.

The manor was also the site of a glorious American victory. Recognizing its strategic location, a few hundred yards from ocean access at Smith Inlet, a deep-water channel nearly a half-mile wide at the time, the British built a triangular fort surrounding the manor using stockade fencing 12 feet high.

Tallmadge was one of the leaders of George Washington’s Culper spy ring (as recently reported here in the Fire Island News – you dare not miss an issue!). He raised a force of 80 unhorsed dragoons who rowed whaleboats for five hours, 15 miles across the Long Island Sound. They then marched 20 miles across greater Long Island in a drenching rainstorm that forced them to delay their attack until their gunpowder dried. At first light they hacked their way through the stockade fence shouting “Washington and glory!” and, after a brief firefight, captured the fort.

Using British cannons and gunpowder, Tallmadge turned the guns on a British warship lying at anchor in the bay and sank it. He then chose a party of 12, commandeered British horses, and rode to Coram where they set fire to a strategic store of hay the British had provisioned there. The next morning they rowed home without the loss of a single American life, and with ample stolen supplies and several prisoners.

After peace was restored by the 1873 Treaty of Paris, William Floyd returned to Mastic to find his plantation nearly destroyed, stripped of all its crops, livestock, timber and household goods. He restored the plantation while at the same time the Smiths rebuilt the Manor of St. George.

William Floyd was involved in politics for much of his life. He often served as presidential elector, was a member of the New York State Senate, and was elected to Congress in the first election under our new Constitution. Upon retirement he held the rank of Major General in the New York State Militia.

Toward the end of his life he devoted his time to his new farm along the Mohawk River in upstate New York. He passed away in 1821 at the age of 86 and is buried there – although his original headstone remains in Mastic.

The Old Mastic House was passed down through nine generations. William Floyd’s great-great-granddaughter, Cornelia Floyd, donated it to the National Park Service in 1976, and it has been meticulously maintained ever since with few changes.

The new exhibit in the Old Mastic House this year celebrates its 300th anniversary. The exhibit showcases the building’s unique combination of Colonial, Victorian and Greek Revival architectural styles. Walk through its 25 rooms and celebrate 300 years of American history from its original post and beam construction, to its 18th century doors, and its 12 over 12 windows. The exhibit features beautiful ceramics, glassware, textiles, documents, etc. that span the centuries.

The original deed for the property is on display – without the purchase price – which remains unknown to this day. There is much to see and learn by taking the hour-long tour, which includes the Vista View, still providing its spectacular panorama of the Great South Bay and Fire Island.The house is open every Friday-Sunday, and Federal holidays, from Memorial Day weekend through Veterans Day. Tours start at 10 a.m. and run to 4 p.m. every half-hour. The tours are free.

On July 7, 2018, starting at 11 a.m., there will be an unveiling of the first-ever historic marker dedicated to the Old Mastic House. The marker is a gift from the Narrow Bay Historical Society. Musicians will be strolling about the grounds playing a variety of colonial and/or civil war songs. There will be an anniversary cake-cutting at noon accompanied by light refreshments. Tours will be conducted as normal.Monumental history was made in the Old Mastic House on the William Floyd Estate. Celebrate the festivities! Remember, it’s free. For information, call 631-399-2030.