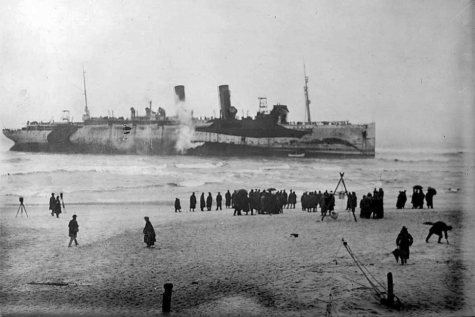

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

No one knows how many wrecks have occurred off Fire Island’s shores, some horrific, some forgotten to history, but the most miraculous rescue must be that of the “U.S.S. Northern Pacific,” which ran aground on New Year’s Day in 1919, with a shipload of wounded soldiers.

The World War I troop carrier left Brest, France, en route to Hoboken, New Jersey, on Christmas Day. On board were more than 2,500 doughboys returning from the war. Of those, more than 1,500 were wounded – 300 bedridden – with 17 Navy nurses in attendance. Designed to carry 856 passengers and a crew of 198, the “Northern Pacific” was carrying more than two and a half times that many individuals, putting all in jeopardy on that fateful voyage.

The ship approached the port of New York on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 1919. It was pouring rain, with winds blowing out of the southwest, and the temperature was a chilling 45 degrees. Monstrous Atlantic Ocean waves pummeled the “Northern Pacific,” breaking over her superstructure and twin smokestacks. She ran aground at 2:20 a.m. on a sandbar approximately 200 yards south of Fire Island. Immediately, attempts were made to back her off the bar, but they proved unsuccessful.

The ship’s master, Captain L. Connelly, promptly sent out an SOS. He was in constant contact by wireless with Captain B.W. Blamer, chief of staff to Admiral Gleaves, coordinating rescue efforts. Despite the grave conditions, Captain Connelly sent a message to reassure the relatives of the returning servicemen that “they need have no fear for their safety.”

Early that morning, U.S. Coast Guardsman Roger Smith sighted the ship a few miles southeast of Fire Island Coast Guard Station 84. Soon a contingent of Coast Guardsmen was on scene firing breeches buoy lines out to the stricken vessel in attempts to affect a rescue. Heavy winds and high seas, however, prevented the shot lines from reaching the ship.

Alerted by the SOS, and with deadly concern for the catastrophic disaster facing the wounded men and their caretakers, numerous vessels immediately made for Fire Island, including the salvage tug “Resolute,” the cruisers “Columbia” and “Des Moines, ” the transport “Henry R. Mallory,” six submarine chasers, and a minesweeper, among others. Throughout the night they kept the “Northern Pacific” illuminated with their searchlights. The hospital ship “Solace” lay offshore ready to accept the injured should weather permit.

The local residents also pitched in to help. A fleet of small boats, both commercial and privately owned, gathered in Bay Shore, ready to transport the stranded victims from Fire Island across seven miles of the Great South Bay to a steam locomotive ready to rush the wounded to the hospital.

Storm warnings issued Wednesday morning by the U.S. Weather Bureau called for high intensity storms extending from Florida to Maine. The storms were moving eastward from the Great Lakes with heavy southerly winds predicted to shift to the west the following day.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

The winds increased throughout the night. One rogue wave swept down the side of the “Northern Pacific,” tearing away a lifeboat from her superstructure. The ship was driven further on shore by the fierce winds and violent seas, twisting her broadside into the sandbar where she came hard aground, listing heavily to her port side, in waters only 10 feet deep. An attempt to tow the 8,000 ton, 524 foot long “Northern Pacific” off the sandbar during the following morning’s high tide failed.

Thirty hours after the “Northern Pacific” ran aground a detachment of Coast Guardsmen was finally able fire a line to the vessel, and began rescue efforts using a breeches buoy apparatus. The line was secured from the ship to the shore where it was anchored to a tripod buried deep in the sand. The line carried a life ring attached to a pulley system, a scheme honed by decades of experience, but one only for the able and the desperate.

Surfboats began ferrying the wounded, 10 at a time, through the rough breakers to the shore. Rescues continued throughout the day and, in spite of the bitter cold and difficult sea conditions, 254 passengers including all 17 nurses were successfully saved. The only casualty was a rescue motor launch from the cruiser “Columbia,” which was swamped and driven ashore. The three men aboard were plucked from the icy waters and resuscitated by Coast Guard sailors.

The weather abated somewhat, Friday, Jan. 3, enabling the rescue of an additional 210 troops. Numerous barrels of oil were spread on the waters in an attempt to calm them, but conditions remained too hazardous to remove those on stretchers, the ones most desperately needing saving. As the weather continued to improve, the submarine chasers with their shallow drafts and high maneuverability were finally able to approach the “Northern Pacific’s” leeward side, and began disembarking the most severely wounded to the hospital ship “Solace,” and the ambulatory to the “Mallory” and other nearby ships. By noon on Saturday, Jan. 4, the last of the wounded men had been safely evacuated.

After three and a half days of intense efforts everyone was saved. The experienced rescuers had proceeded deliberately, with patience and due caution, and, miraculously, there were no major injuries and not a single life was lost.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

With all the troops safely removed, efforts turned to refloating the “Northern Pacific.” Barges and lighters came alongside and, using their powerful winches, removed the “Northern Pacific’s” guns, her lifeboats and signal towers – anything heavy – to lighten the load. Three tugs fastened to her stern and pulled the ship seaward at each successive high tide. Progress was slow, gaining a few feet, before losing some, but she was finally broken free of the sandbar and refloated on the evening of Jan. 18, two and a half weeks after her initial grounding. The Coast Guard maintained a continuous vigil during the entire ordeal.

Repairs to her damaged bottom plates and rudder required five months of work before the “Northern Pacific” could return to duty. Subsequently, she made two more trans-Atlantic voyages.

Three years later, in February of 1922, while being towed to a shipyard in Pennsylvania, the “Northern Pacific” caught fire, capsized and sank in 150 feet of water, 30 miles south of Cape May, New Jersey, where she remains to this day, a favorite haunt for wreck divers.