Lurking in the depths of over 700 feet within the murky Atlantic, a predator stalks its prey. Moving its 251-foot length slowly and carefully, it attacks with stealth. Some will live to report the horrors accompanied by the element of surprise, which would mobilize the military to launch a manhunt lasting four years to destroy U-boat 123.

Following Dec. 7, 1941, attacks on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. entered World War II. With our entry into the war, we became embodied in brutal naval combat with Germany, Japan, and their allies. To weaken our nation’s morale and supply lines to its allies, Nazi German commanders organized U-boat attacks along the east coast of the United States in the shadows of major cities.

This campaign was code name Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat). Selected for the mission was Reinhard Hardegen, who was given command of U-boat 123 and assigned to hunt along the east coast. On Jan. 14, 1942, at 8:53 a.m., the war came to the shores of Long Island.

The oil tanker “Norness” was sailing 60 miles offshore of Montauk Point and Block Island when it was torpedoed. The “Norness” capsized, killing two crew members. Later in the afternoon, 39 surviving crew members were spotted and rescued by the Coast Guard Cutter “Argo.”

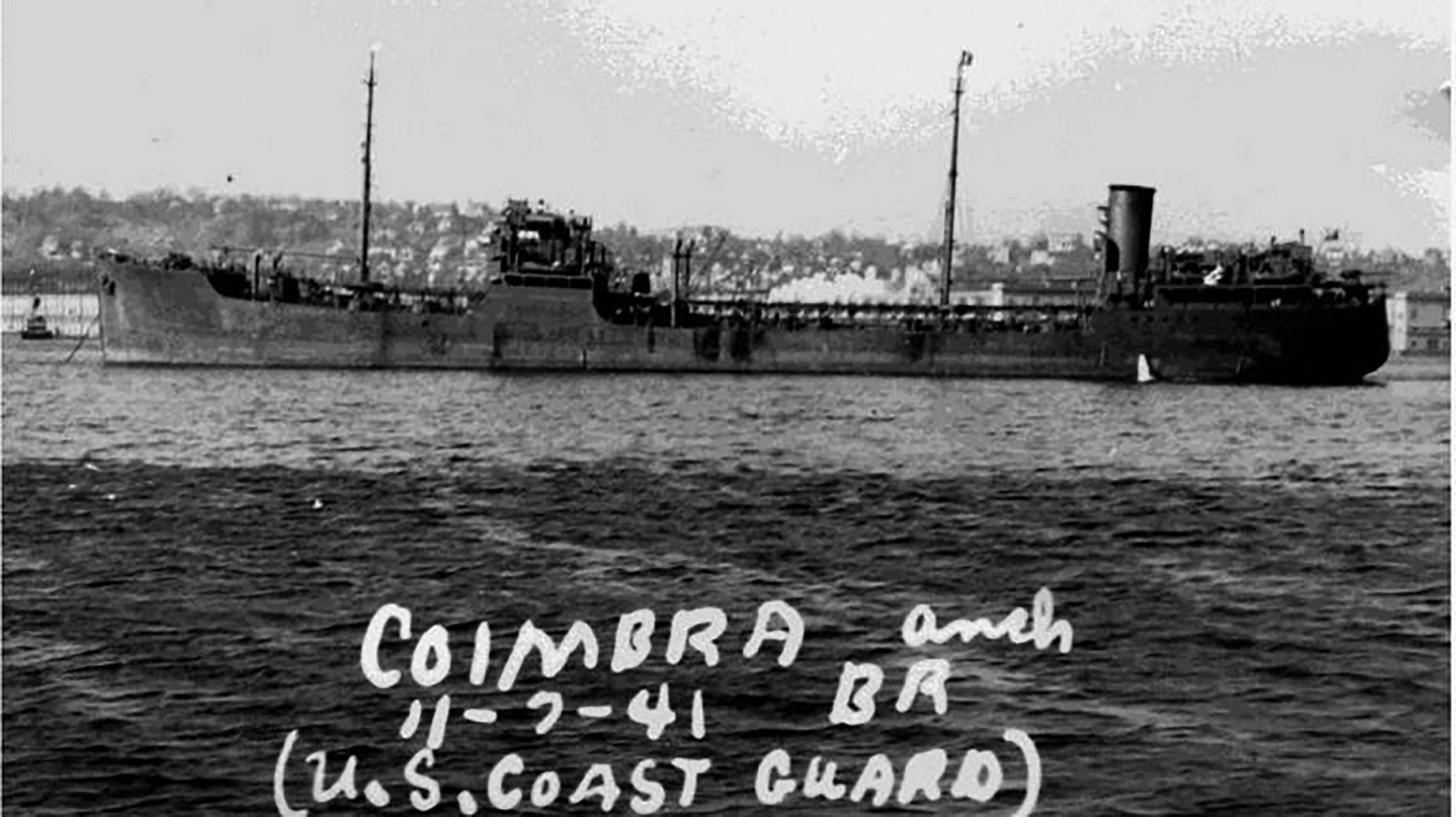

Before the newspapers reported the sinking, the oil tanker “Coimbra” was torpedoed 36 hours later, 20 miles off the coast of Quogue. Of the crew of 46, only 10 would survive the attack. Both tankers were en route from New York or New Jersey to England. Following the attacks, local Navy installations and Army Air Force Mitchel Field base in Uniondale mobilized U-boat patrols off the coast of Long Island and around New York Harbor. Despite the efforts of the military and the odds of three out of four U-boat crew members being killed, U-boat 123 was not found.

The “Coimbra,” an oil tanker believed to have been sunk off the coast of Suffolk County by U-Boat 123, an incident with many casualties. (Image from U.S. Library of Congress)

While under the command of Hardegen, a confirmed total of 21 boats were sunk, and five were severely damaged. With the looming threats, towns and villages across Nassau and Suffolk Counties had routine air raid and blackout drills. The blackout drills were designed to throw off attacks at night through air or sea by not providing visible targets. On March 25, 1942, the Civilian Defense Corps conducted the first successful large-scale drill for the 331 square miles of the entire Nassau County. Successfully carrying out the blackout drills depended on air raid wardens to mobilize the locals. New York set a goal of one air raid warden for every 125 people.

Towards the end of the war, the fears of U-boat raids grew with the introduction of the V-1 rocket. On Jan. 9, 1945, a Newsday interview with Navy Admiral Jonas Ingram warned that “there could be as many as 300 U-boats in the Atlantic and only six or eight of these boats are needed to launch bombs from Montauk into New York City.” Based on these fears, at the close of the war, one in four residents of Nassau County was in the Civilian Defense Corps.

The deadliest part of U-boat 123 was its commander’s ability to navigate the proximity of New York harbors. In an interview with American filmmaker Stephen Ames in 1992, Hardegen stated, “It was very easy navigation for me. I used landmarks such as the WOR radio tower in Coney Island, lights along the south shore, and a New York City tourist book.” In later interviews with German author and historian Karl Hoffkes, Hardegen would clarify he did not serve Hitler but Germany and elaborated he was a critic of Hitler.

By July 1942, Hardegen gave up his command of U-boat 123 and was awarded the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves. After the war, Hardegen got into the home heating oil business working with Texaco oil company, the same oil company that leased many of the tankers Hardegen sunk decades earlier.