History

By Thomas McGann “Backward ran sentences until reeled the mind,” reads Wolcott Gibbs’ parody of Time magazine, an article that is still highly touted, so much so that it tends to obscure much of what else he wrote, and write he did. Gibbs concluded his lampoon, “Where it all will end, knows God!”Gibbs wrote for The New Yorker from 1927 until his death in 1958. He was an editor, a theatre critic, an author of short stories, a Broadway playwright, a humorist with a wicked wit, and he was a Fire Islander.He was also a condescending curmudgeon, an unhappy boy who grew into a less happy man. He came from a family that once had bucks but then had none, a family that fought to protect its highbrow pedigree. He was named after Oliver Wolcott, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and also a direct descendant of Martin Van Buren, president of the United States. But then his father had to go and die on him when he was only 6, and his mother lost custody of her own children because she was a drunk, so he and his sister were raised by a bachelor uncle who never settled down, took them everywhere and nowhere. If only he’d gone to college! He complained so often his friends threatened to raise enough money to send him to Yale for a weekend just to shut him up. No wonder Gibbs became known for his disdain of his fellow man, and for his cheeky rudeness. He once wrote, “I wonder if there is something the matter with me that I can’t like anybody for long.” He was never happy – never happy, that is, except on Fire Island.He found Fire Island as a child, sailing over one day with some cousins and that was it. It was like falling in love with the perfect woman, not that that ever happened to him of course. He was married three times. First time was a hit with a Miss too young – neither of them ever spoke of it afterwards. Second time he was already a dandy- drudge with damaged dreams. Three years of marriage hell until she threatened to jump out the 17th story window; he told her to go ahead and she did. Third time’s a charm it’s said. Well, certainly not charmed for Gibbs. Maybe he and Elinor loved each other, but then again maybe not. They sure loved getting sloshed together and get sloshed they did.

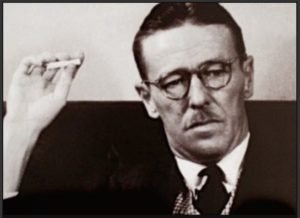

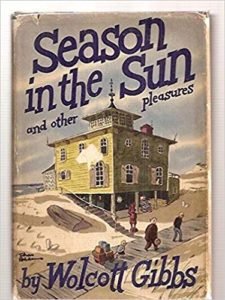

“Backward ran sentences until reeled the mind,” reads Wolcott Gibbs’ parody of Time magazine, an article that is still highly touted, so much so that it tends to obscure much of what else he wrote, and write he did. Gibbs concluded his lampoon, “Where it all will end, knows God!”Gibbs wrote for The New Yorker from 1927 until his death in 1958. He was an editor, a theatre critic, an author of short stories, a Broadway playwright, a humorist with a wicked wit, and he was a Fire Islander.He was also a condescending curmudgeon, an unhappy boy who grew into a less happy man. He came from a family that once had bucks but then had none, a family that fought to protect its highbrow pedigree. He was named after Oliver Wolcott, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and also a direct descendant of Martin Van Buren, president of the United States. But then his father had to go and die on him when he was only 6, and his mother lost custody of her own children because she was a drunk, so he and his sister were raised by a bachelor uncle who never settled down, took them everywhere and nowhere. If only he’d gone to college! He complained so often his friends threatened to raise enough money to send him to Yale for a weekend just to shut him up. No wonder Gibbs became known for his disdain of his fellow man, and for his cheeky rudeness. He once wrote, “I wonder if there is something the matter with me that I can’t like anybody for long.” He was never happy – never happy, that is, except on Fire Island.He found Fire Island as a child, sailing over one day with some cousins and that was it. It was like falling in love with the perfect woman, not that that ever happened to him of course. He was married three times. First time was a hit with a Miss too young – neither of them ever spoke of it afterwards. Second time he was already a dandy- drudge with damaged dreams. Three years of marriage hell until she threatened to jump out the 17th story window; he told her to go ahead and she did. Third time’s a charm it’s said. Well, certainly not charmed for Gibbs. Maybe he and Elinor loved each other, but then again maybe not. They sure loved getting sloshed together and get sloshed they did. His one true love, the novelist Nancy Hale, had to be a married woman, of course, with a son of her own. The affair was brief (she broke it off, of course), but he continued to write love notes for years. “I am never going to be in love with anybody but you,” he wrote, “and I suppose I might as well get used to the idea in spite of all the nervous breakdowns it gives me.” He shared his love affair with Fire Island with her too. “I am a child of the sun, and in the summer I am happy, singing from morning till night, but when it gets cold I die.” She never responded, of course. He was a successful writer. In his role as a critic, he wrote the most succinct review of a play ever. The play was called “Wham!” and his critique was “Ouch!” Another oft quoted review was of William Saroyan’s “The Beautiful People.” Gibbs opened by describing “a set that might have been executed by Salvador Dali, needing, in fact, only a rubbery watch and a couple of lamb chops.” But writing reviews, even for plays on Broadway, he shook his head, was no way for a serious writer to make a living.Oh yeah, there was his Broadway play, “Season in the Sun.” It was an accumulation of his stories written for The New Yorker, about, yep, you guessed it, Fire Island. It ran for 10 months – not bad. Not “Guys and Dolls,” mind you, but counting money is so boorish anyway.Giants of his time heaped praise. E.B. White (author of “Charlotte’s Web”) wrote, “Professionally ambidextrous: a natural editor, a prolific and good and versatile writer – gifts rarely combined in one person.” Harold Ross, founder of The New Yorker said, “Maybe he doesn’t like anything, but he can do everything.” P.G. Wodehouse (“My Man Jeeves”) considered The New Yorker “the dullest bloody thing ever published … except for Wolcott Gibbs.” In admiration of his nasty witticisms James Thurber (author of “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”) wrote, “When Wolcott Gibbs set out to do ‘a job’ on a profile subject, he brought out a fine array of surgical instruments, a rapier, and a pearl-handled blackjack.”Gibbs was good for a few hours at a party, not that he enjoyed parties – hated them – all that mixing with his inferiors, most of whom did not possess enough manners to leave him to his booze. He hated introductions “obliging him to know people he would rather avoid.” “Every man seems threatening to become my brother or better,” he complained. Didn’t anyone read Emily Post anymore, for chrissakes? A couple of hours of free-flowing booze and he was liquefied. His friends would pour him into the backseat of a taxi for the black-out home. The only problem was putting all the disconnected memories back together again the next day. His insults, he remembered, were always the acme, were never banal. He left that to lesser men.Fire Island was the only lady who ever made him happy – yes, happy. “I’m in love with the goddamn beach!” he crowed. He loved the sun and the sand, cigarettes, and martinis. He would mix a shaker full, take it to the beach and bury it up to its neck in the sand. He’d lie in the sun, chain-smoking cigarettes, and drinking of course. He’d sunbathe all day, tanning his skin, and bleaching his hair. Russell Maloney, one of his drinking buddies, remarked that Gibbs looked like a “photographic negative” of himself, which, of course, he was. But at least the island made him happy. A curmudgeon mellowed by Fire Island. He even started a local paper, The Fire Islander, where he tempered his sardonic edge with, dare it be said, almost sunny copy. He enlisted his comrades from The New Yorker in his new endeavor. Got them to write pieces for his baby. Never paid them, of course, but he would take them out to lunch occasionally.His paper was genuinely concerned about his island – ever so serious about it. The dunes! The dunes were crucial to the stability of the beach. And tennis courts were a great idea. Good exercise before hitting the beach with the booze and the butts. Had to put an end to those low flying military jets too, pilots with their stiff erections blasting across the broken-blue skies of his island. Didn’t they realize they were ruining it for everyone?He ran the paper for three years, but was fading away. His writing “was wearing very thin,” he admitted. He’d lost it. He sold the paper to some local boys (did he or didn’t he?) promising he, and his executives, would toss a piece or two their way just for old time’s sake. “Beyond that,” he wrote, “[I am] as dead as so many dinosaurs. It may be just as well.”Gibbs died on Fire Island. Elinor found him dead in bed, an advance copy of his latest book open on his chest, a cigarette dangling between his fingers. The doctor faked an autopsy because Elinor was afraid it was a suicide.Wolcott Gibbs was gone. He was 56.John O’Hara remarked, “…he is all the proof you need that things do not even up in the end. They never evened up for him.” Where it all ended knows God.At least Fire Island had made him happy. He loved this goddamn island. Editor’s Note: The original print version of this article, published in the August 17, 2018, edition of Fire Island News, the photographer for the image of Wolcott Gibbs was listed as “unidentified,” as we could not locate an attribution at the the time. Shortly after, Long Island-based Author Thomas Vinciguerra informed us that renowned German-born photographer, Hilde Hubbuch, who lived from 1905-1971, took this portrait. Thomas Vinciguerra is the author of two books that chronicle the life of Wolcott Gibbs, “Backward Ran Sentences” (Bloomsbury, 2011) and “Cast of Characters” (W.W. Norton & Co., 2015). Both of these works were among the sources Mr. McGann referenced in compiling his article.

His one true love, the novelist Nancy Hale, had to be a married woman, of course, with a son of her own. The affair was brief (she broke it off, of course), but he continued to write love notes for years. “I am never going to be in love with anybody but you,” he wrote, “and I suppose I might as well get used to the idea in spite of all the nervous breakdowns it gives me.” He shared his love affair with Fire Island with her too. “I am a child of the sun, and in the summer I am happy, singing from morning till night, but when it gets cold I die.” She never responded, of course. He was a successful writer. In his role as a critic, he wrote the most succinct review of a play ever. The play was called “Wham!” and his critique was “Ouch!” Another oft quoted review was of William Saroyan’s “The Beautiful People.” Gibbs opened by describing “a set that might have been executed by Salvador Dali, needing, in fact, only a rubbery watch and a couple of lamb chops.” But writing reviews, even for plays on Broadway, he shook his head, was no way for a serious writer to make a living.Oh yeah, there was his Broadway play, “Season in the Sun.” It was an accumulation of his stories written for The New Yorker, about, yep, you guessed it, Fire Island. It ran for 10 months – not bad. Not “Guys and Dolls,” mind you, but counting money is so boorish anyway.Giants of his time heaped praise. E.B. White (author of “Charlotte’s Web”) wrote, “Professionally ambidextrous: a natural editor, a prolific and good and versatile writer – gifts rarely combined in one person.” Harold Ross, founder of The New Yorker said, “Maybe he doesn’t like anything, but he can do everything.” P.G. Wodehouse (“My Man Jeeves”) considered The New Yorker “the dullest bloody thing ever published … except for Wolcott Gibbs.” In admiration of his nasty witticisms James Thurber (author of “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”) wrote, “When Wolcott Gibbs set out to do ‘a job’ on a profile subject, he brought out a fine array of surgical instruments, a rapier, and a pearl-handled blackjack.”Gibbs was good for a few hours at a party, not that he enjoyed parties – hated them – all that mixing with his inferiors, most of whom did not possess enough manners to leave him to his booze. He hated introductions “obliging him to know people he would rather avoid.” “Every man seems threatening to become my brother or better,” he complained. Didn’t anyone read Emily Post anymore, for chrissakes? A couple of hours of free-flowing booze and he was liquefied. His friends would pour him into the backseat of a taxi for the black-out home. The only problem was putting all the disconnected memories back together again the next day. His insults, he remembered, were always the acme, were never banal. He left that to lesser men.Fire Island was the only lady who ever made him happy – yes, happy. “I’m in love with the goddamn beach!” he crowed. He loved the sun and the sand, cigarettes, and martinis. He would mix a shaker full, take it to the beach and bury it up to its neck in the sand. He’d lie in the sun, chain-smoking cigarettes, and drinking of course. He’d sunbathe all day, tanning his skin, and bleaching his hair. Russell Maloney, one of his drinking buddies, remarked that Gibbs looked like a “photographic negative” of himself, which, of course, he was. But at least the island made him happy. A curmudgeon mellowed by Fire Island. He even started a local paper, The Fire Islander, where he tempered his sardonic edge with, dare it be said, almost sunny copy. He enlisted his comrades from The New Yorker in his new endeavor. Got them to write pieces for his baby. Never paid them, of course, but he would take them out to lunch occasionally.His paper was genuinely concerned about his island – ever so serious about it. The dunes! The dunes were crucial to the stability of the beach. And tennis courts were a great idea. Good exercise before hitting the beach with the booze and the butts. Had to put an end to those low flying military jets too, pilots with their stiff erections blasting across the broken-blue skies of his island. Didn’t they realize they were ruining it for everyone?He ran the paper for three years, but was fading away. His writing “was wearing very thin,” he admitted. He’d lost it. He sold the paper to some local boys (did he or didn’t he?) promising he, and his executives, would toss a piece or two their way just for old time’s sake. “Beyond that,” he wrote, “[I am] as dead as so many dinosaurs. It may be just as well.”Gibbs died on Fire Island. Elinor found him dead in bed, an advance copy of his latest book open on his chest, a cigarette dangling between his fingers. The doctor faked an autopsy because Elinor was afraid it was a suicide.Wolcott Gibbs was gone. He was 56.John O’Hara remarked, “…he is all the proof you need that things do not even up in the end. They never evened up for him.” Where it all ended knows God.At least Fire Island had made him happy. He loved this goddamn island. Editor’s Note: The original print version of this article, published in the August 17, 2018, edition of Fire Island News, the photographer for the image of Wolcott Gibbs was listed as “unidentified,” as we could not locate an attribution at the the time. Shortly after, Long Island-based Author Thomas Vinciguerra informed us that renowned German-born photographer, Hilde Hubbuch, who lived from 1905-1971, took this portrait. Thomas Vinciguerra is the author of two books that chronicle the life of Wolcott Gibbs, “Backward Ran Sentences” (Bloomsbury, 2011) and “Cast of Characters” (W.W. Norton & Co., 2015). Both of these works were among the sources Mr. McGann referenced in compiling his article.