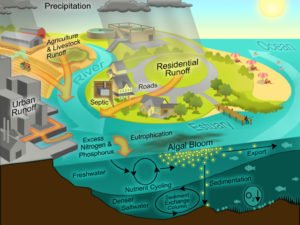

By Anika LanserA proposed law that seeks to amend the environmental conservation legislation in the state of New York has created an interesting divide between its supporters and rivals, both of whom are using environmental arguments to justify their positions on the regulation. The law would ban the sale and use of any fertilizer other than low-nitrogen fertilizer. According to the legislation, low-nitrogen fertilizer can be classified as “containing not more than twelve percent nitrogen by weight, of which at least half must be water insoluble nitrogen, commonly referred to as slow release of nitrogen.” The law would require retailers to stop selling high-nitrogen fertilizers by Dec. 31, 2019, giving stores almost a year and a half to find low-nitrogen fertilizers to sell instead.However, some oppose the bill, saying that it is not as environmentally-conscious as it seems. One such group is the Long Island Coalition for Healthy Lawn and Water. The group’s Facebook page urges Long Islanders to lobby their senators to vote no on the ban. One post reads, “The possible ban on most lawn and garden products would have a devastating impact on residential and community areas like houses, parks, schools, and athletic fields. The bill, which would single out Long Islanders, was overwhelmingly REJECTED in Suffolk County and Nassau County never even sought to introduce the measure. The net impact would unfairly lead to far less effective lawn and garden care products at far higher prices for residents on Long Island without improving local water quality.”It is not immediately clear exactly who the Long Island Coalition for Healthy Lawn and Water actually is. Except for a Facebook page with a little over 200 followers, there are no officers or even a mailing address cited, nor does Guidestar list them as a registered 501(c)3 organization.The response of other groups, like Save the Great South Bay and Seatuck Environmental Association, falls further towards the other side of the spectrum, supporting the bill as a first step by acknowledging how much other work needs to be done in terms of improving water quality to protect the bay and the wildlife it supports. Maureen Dunn, water quality scientist at Seatuck Environmental Association, argues, “If you have a healthy lawn and you fertilize it, that lawn and the plants will absorb a lot of toxins in runoff, will take up a lot of water, and will decrease the amount of sediment and dirt that gets washed away. That’s all true, but that implies that you have given that lawn exactly the amount of nitrate that it needs and not a drop more. That’s very difficult, nearly impossible to do. That argument assumes that you need a high-nitrogen fertilizer to have a healthy lawn, which you don’t.”Most of the problems with nitrogen in fertilizers occur when the form of nitrogen most found in fertilizers, nitrate, becomes soluble, says Dunn. This allows the nitrate to end up in the groundwater and proceed virtually unstopped to streams, rivers, and ultimately, the bays. Runoff from lawns occurs mostly when grass is given more nitrogen than it needs to grow via fertilizers, leaving the excess nitrate to end up in the groundwater after heavy rain. Excess nitrate in the bay can lead to a number of other environmental concerns like unhealthy algal blooms often in the form of brown tide, loss of sea grass beds, declines in fish populations, and erosion of salt water marshes. These concerns in turn lead to other environmental issues in the bay, as is the nature of any ecosystem disturbance. As Dunn put it, “Without healthy water, we don’t have healthy wildlife so that’s why water quality is so important.” There are already some laws in place that aim to reduce the amount of nitrogen in runoff and wastewater via regulations like limiting the times of year when fertilizer can be applied. However, Marshall Brown, co-founder of Save the Great South Bay, says that those laws are not doing enough. He argues, “The laws that are currently on the books seem designed to prevent any real change. The rules are hopelessly complex for the homeowner to figure out how much fertilizer should be applied and where. The fertilizer makers don’t really have to do anything in terms of changing their products or their production. The emphasis is really put on the homeowner to do it right and when nitrogen shows up the homeowner is blamed.” In contrast, a law that bans the sale of high-nitrogen fertilizer has the potential to entice fertilizer companies to create options that rely more on slow release technology and a low-nitrogen formula.Brown hopes that this law has the possibility to prevent the added effects that occur when the nitrogen from fertilizer season interacts with a bay already struggling with nitrogen from issues with wastewater treatment. He noted, “Sixty-nine percent of the nitrogen in the bay is from cesspools and septic tanks but the nitrogen that comes into the bay from fertilizer only happens during the part of the year when people are fertilizing their lawns. It’s like throwing kerosene on the fire when all of that nitrate runoff from lawns hits the bay. I would hope that this legislation would prevent the algal blooms from being further exacerbated by that.”This report was updated on May 6, 2020.

There are already some laws in place that aim to reduce the amount of nitrogen in runoff and wastewater via regulations like limiting the times of year when fertilizer can be applied. However, Marshall Brown, co-founder of Save the Great South Bay, says that those laws are not doing enough. He argues, “The laws that are currently on the books seem designed to prevent any real change. The rules are hopelessly complex for the homeowner to figure out how much fertilizer should be applied and where. The fertilizer makers don’t really have to do anything in terms of changing their products or their production. The emphasis is really put on the homeowner to do it right and when nitrogen shows up the homeowner is blamed.” In contrast, a law that bans the sale of high-nitrogen fertilizer has the potential to entice fertilizer companies to create options that rely more on slow release technology and a low-nitrogen formula.Brown hopes that this law has the possibility to prevent the added effects that occur when the nitrogen from fertilizer season interacts with a bay already struggling with nitrogen from issues with wastewater treatment. He noted, “Sixty-nine percent of the nitrogen in the bay is from cesspools and septic tanks but the nitrogen that comes into the bay from fertilizer only happens during the part of the year when people are fertilizing their lawns. It’s like throwing kerosene on the fire when all of that nitrate runoff from lawns hits the bay. I would hope that this legislation would prevent the algal blooms from being further exacerbated by that.”This report was updated on May 6, 2020.