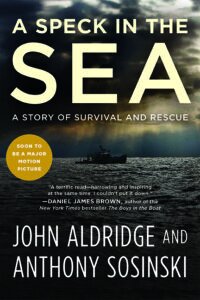

“A Speck in the Sea: A Story of Survival and Rescue” by John Aldridge and Anthony Sosinski

Non fiction

Hachette Books

Man overboard! Montauk lobsterman John Aldridge only wished someone had shouted out that little missive the summer evening of 2013. But when the skilled sailor (he was a fisherman for two decades) slid off the flat open stern and into the sea while preparing his boat for a night of fishing, the two-man crew was “dead asleep and snoring” in the nose of the boat. The required life vest, a safety must aboard every commercial fishing boat?

“We never wear ours,” Aldridge said, recounting his near-drowning almost four years ago. Without flourish or fanfare, in no-nonsense, straightforward prose, “A Speck in the Sea” looks back on Aldridge’s plunge into the dark early morning waters off the coast of Montauk, and his rescue 12-1/2 hours later. A long time to be in the North Atlantic without a flotation device; most don’t survive more than a few hours. Chapters alternate between Aldridge’s account of his misadventure and a third person narrator who supplies backstory on his life, and that of Anthony Sosinski, Aldridge’s childhood friend and co-owner of the lobster boat, “Anna Mary.” Readers will learn about Montauk as a fishing village in the shadow of the well-heeled Hamptons, and the grueling and often hazardous business of men who fish for a living. The waters off the northeast coast are the most dangerous fishing grounds in America.

“You stand in smelly fish slime … tangled miles of rope on a rocking and rolling boat … fifteen hours at a stretch … big sweaty rubber gloves hauling metal traps [hundreds of them] up from the ocean floor.”

Aldridge was in the water for 3-1/2 hours before Sosinski called the Coast Guard to report him missing. A combination of teamwork and technology, of maps and charts and video screens, the search was on. First Montauk sent a patrol boat. The U.S. Coast Guard dispatched helicopters, and fired up SAROPS (Search and Rescue Optimal Planning System). This program divides an area into patterns, and assigns each vessel a zone to search – in Aldridge’s case it was an S-shaped pattern in a rectangular form going north to south. From the wheelhouse of the “Anna Mary,” Sosinski directed a growing armada of volunteer, professional and sport fishermen. But search doesn’t equal rescue, as John Aldridge lamented, bobbing like a buoy in the vast and unforgiving sea, frantically waving his arms and screaming, sighting planes and boats that did not see him. There were sharks less than 10 feet from him. They swam away. Phew! Close one.

Aldridge’s aptitude for single mindedness and positive thinking, his years as a fisherman, of getting the job done allowed him to focus on staying calm (and alive). He tried for images that would bring some normalcy to those hours in the water, something to “lift the misery.” He thought about a vacuum cleaner on his porch. A fisherman with a vacuum cleaner is an incongruous image but there it was: “…. a Eureka? a Hoover? a Bissel?…bag pretty full?” And it helped him. “Swim, rest, swim, rest. Rest, swim again.” Flutter kicks, frog kicks, side crawl, breast stroke.

“Keep going. Endure.” Aldridge knew the waters that held him prisoner, its currents and fluxes. He knew to kick off his rubber boots (first thing you do when you’re in the drink so they don’t weigh you down), upend them, tuck each under an arm, and he had a pair of pontoons to help keep him afloat. He pulled off his socks and pulled them over his hands. They gave him webbing so he could catch more water. He cut loose a buoy to keep him on the water instead of in it.

It’s not on me to take away a reader’s pleasure and reveal how Aldridge was finally rescued. For that you will have to read the book. But I will tell you this: I was so moved when it happened, I cried. And next time I sit down to a seafood dinner and dunk a bit of lobster meat into drawn butter, I will recall the one special lobsterman who may have put the crustaceous critter on my plate.

Aldridge’s recovery from his trauma is discussed in the epilogue. He is a spokesman for boat safety. Ironically, he still does not wear a life jacket when fishing. He claims most commercial fisherman do not. They’re “too bulky and uncomfortable when you’re hauling traps.” But there is a gate on the stern of the “Anna Mary” now, and no one is ever alone on deck. A movie on his experience is in the works. Personal photos accompany the text.