A true monarch. Photo by Bob Anderson

The wonderfully colorful monarch (Danaus plexippus), also known as “common tiger” or “wanderer,” is probably the most familiar of North American butterflies. This elegant creature is frequently seen on Fire Island during its late summer southern migration.

Monarchs feature a distinctive black, orange, and white wing pattern, spanning about four inches (10 cm). They are thought to have been named in honor of King William III of England because the butterfly’s color is that of the king’s secondary title, the Prince of Orange.

Variants of the monarch are found nearly world-wide, including in most of South and Central America, Europe, parts of Asia, Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands. There’s even a white monarch on the Hawaiian Islands. And in 2009, monarchs were reared on the International Space Station in its bioprocessing facility!

Eastern North American males have larger wings than females and are typically heavier. But females have thicker stronger wings giving them greater damage resistance and an ability to fly using a bit less energy.

Monarchs have an impressive visual system somewhat similar humans, with a retina containing three types of photoreceptors. But unlike us, they can also see into the ultraviolet, and via special filter pigments, in the shorter infrared range as well.

Beyond mere perception, the ability to remember certain colors is essential in the life of monarch butterflies. These insects can easily learn to associate color and shape with sugary foods. When searching for nectar, color is the first cue that draws the insect’s attention toward a potential food source, and shape is a secondary characteristic promoting the process. When searching for a place to lay its eggs, the roles of color and shape are switched.

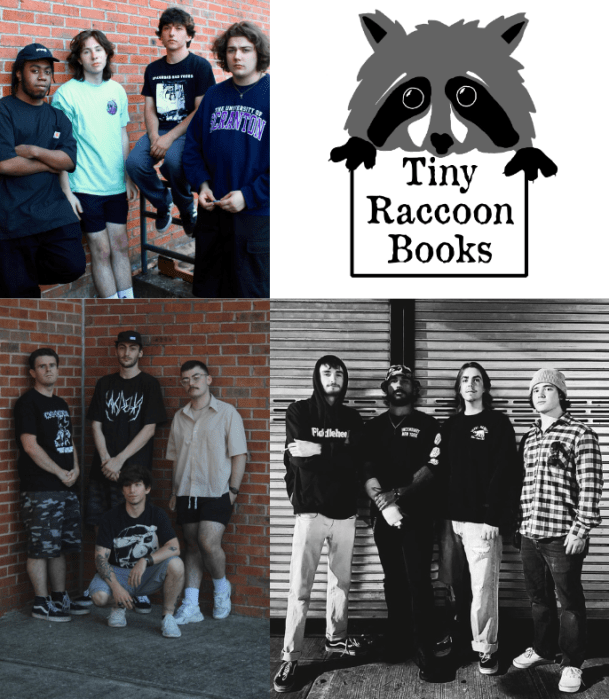

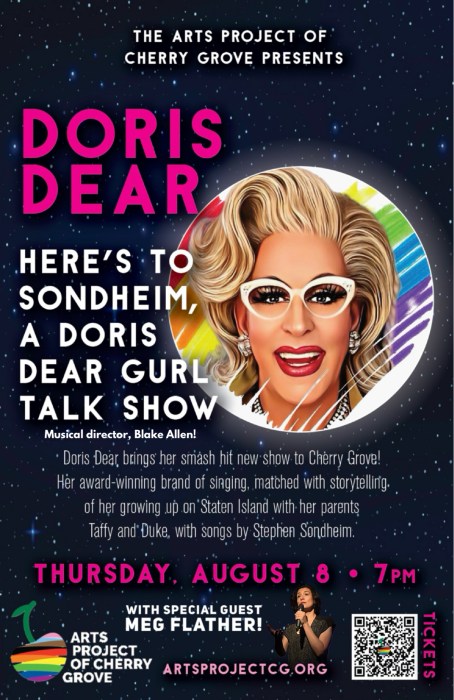

Painted lady. Wikipedia

Adult monarchs feed on the nectar of many plants, including milkweed, coneflower, hemp, aster, wild carrot, teasel, horseweed, boneset, alfalfa, goldenrod, lilac, red clover, and ironweed. Of these species, milkweeds are by far the most important for monarch survival. As for water, monarchs obtain moisture (and minerals) from damp soil and wet gravel, a behavior known as mud-puddling.

A similar butterfly is sometimes mistaken for the monarch: the painted lady (Vanessa cardui, see picture), the most widespread species, present on every continent except Antarctica and South America. It’s common in Europe, and variants occur on the U.S. west coast. In Europe it has an even longer migration pattern than the monarch, extending from North Africa to almost the Arctic Circle, and journey at least a 1,000 miles longer than the monarch. Curiously, painted lady butterflies have a visual system that resembles that of a honey bee with receptors for ultraviolet, blue, and green. But unlike the monarch, painted ladies can’t see red. This influences their choice of host plants, of which there are more than 300, but mostly not milkweed, so monarchs have no real competition from painted ladies.

The monarch was the first butterfly to have its genome sequenced. It was found to contain over 273 million base pairs. This provided insight into migratory behavior, the circadian clock, juvenile development and coloration. It also was discovered that there’s little genetic difference between the migratory populations of eastern and western North America.

The eastern North American monarch population is notable for its annual southward late-summer migration from the northern United States and southern Canada to Florida and Mexico. During the fall migration, monarchs cover thousands of miles! Monarch populations west of the Rocky Mountains often migrate to sites in southern California, but individuals have been found in overwintering Mexican sites.

Monarch migration. Map by Bob Anderson

But wait a minute … how’s it possible for them to survive a round-trip journey of 5,000 miles? Relative to body size, that’s like asking you to walk around the earth four times, twice a year! Can it really be that such a delicate creature – a given individual – can make it all the way from Mexico to Maine, soar around all summer, and then fly all the way back again?

In our next issue we’ll explore the surprising answer to that question, taking a closer look at their life cycle to discover how they pull off such a journey. Then we’ll explore what you can do to help this amazing creature survive and prosper!

In our next issue we’ll explore the surprising answer to that question, taking a closer look at their life cycle to discover how they pull off such a journey. Then we’ll explore what you can do to help this amazing creature survive and prosper!