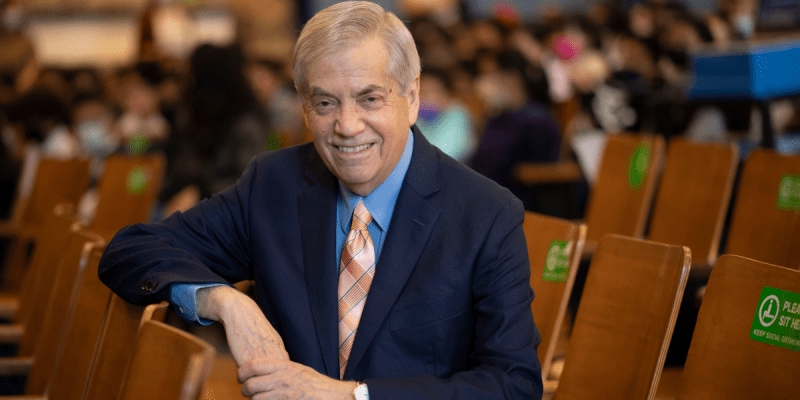

Fire Island Ferry Company President Tim Mooney makes waves beyond the Great South Bay. According to the United States Coast Guard’s most recent yearly data, there were 2126 injuries and 564 deaths from ferry and recreational boating accidents in 2023. Overall, these dire stats have been unchanged over the past 20 years. However, since its establishment in 1948, Fire Island Ferries has prided itself on a flawless safety record year after year. Starting as an 18-year-old deck hand on one of the fleet’s freight vessels, Edward Mooney and his partners purchased the company in 1970 from founders Elmer Patterson, Bill White, and Ed Davis for $150,000. Following his purchase, Edward phased out wooden ferries and replaced them with steel ferries equipped with radar, modernizing the fleet. These modernization efforts expanded the ferry service to 28 vessels, which served over a million passengers annually. Since then, the Mooney family has focused on improving local and international ferry safety. Following in his father’s footsteps, Fire Island Ferry Company President Tim Mooney is also the chairman of Interferry, a non-profit organization dedicated to improving safety, equitable regulations, and environmental protection worldwide. Interferry has 270 member companies from 40 countries, and collectively represents all ferry operators in the United Nations International Maritime Organization (IMO). We sat down with Tim to ask some questions and gain more insight into how the Fire Island Ferry Company’s safety practices influence global safety protocols.

Great South Bay News (GSBN): How did you get involved with Interferry?

Tim Mooney (TM): My father was one of the founding members in 1976. I became a board member in 2013 and have served as chairman for the past three years.

GSBN: Before your work with Interferry, you had a background in technology. How does your technology background help guide your role as president of the Fire Island Ferry Company and chairman of Interferry?

TM: Eight years ago, we launched an app that offers digital ticketing for our ferry and water taxi services. The app operates on the same platform as the Long Island Rail Road MTA app. The success of this rollout has sparked discussions regarding ticketing and even passport control, particularly for international ferry tracking. This field has become highly technological, which is crucial for efficiency.

GSBN: What is the most significant global safety challenge?

TM: Ensuring government involvement in establishing safety protocols and enforcing regulations. Many countries lack the necessary oversight infrastructure, such as a Coast Guard, which leads us to hope that operators will collectively self-police. We recently completed a collaboration with Indonesia and the Philippines on new safety protocols. Next, we will work with the Maritime Organization for West and Central Africa (MOWCA) to develop a safety protocol in Nigeria this year.

GSBN: Nigeria has experienced multiple ferry disasters in the past year, including the capsizing of three vessels in October, November, and January, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of people. Can these disasters be prevented? What are the primary causes of these tragedies?

TM: It’s disheartening to read about people who have died in ferry disasters. Ferry safety in Lagos, Nigeria, can be improved. These situations can be challenging to manage due to weather conditions, excess weight, or poor modifications. Many operators purchase older boats from the United States or Europe, modify them by cutting them in half, welding in an extension, and removing benches. These wider ferries can accommodate more passengers, but unlike in the United States, the work is not engineered or inspected for safety, nor is there an established maximum weight limit.

GSBN: How does Interferry implement a new safety protocol?

TM: MOWCA and the Nigerian government have reached out to us. We pay the operators to attend, listen to their challenges, and collaborate. Operations can be offshore, on lakes, or on rivers, and we match them with the resources that best fit their needs. These needs include terminal layouts for moving people or cargo, ticketing, and safer boat modifications.

GSBN: What safety requirements do you use for modifications and weight max?

TM: When we have a boat built, the plans are sent to the Coast Guard for review. While the ship is being constructed, the Coast Guard inspects the work. Once completed, the boat must go through a series of safety trials. For weight capacity, we estimate the weight of passengers on the ferry to be 185 pounds—women, children… everyone. We take the number of passengers and multiply it by 185, then reference it against the maximum capacity.

GSBN: Can you provide an example of how the Fire Island Ferry Company adapted to a recent challenge?

TM: During COVID, we had to redesign our terminal layout to reduce traffic flow. We became more efficient at moving people and preventing crowds at the terminal. We staggered ferry schedules. This not only stopped crowds from building up but also reduced traffic on Maple Avenue.

GSBN: How is the Fire Island Ferry Company updating its fleet to meet future environmental challenges?

TM: We are upgrading our old diesel engines to the EPA Tier III motors, which run cleaner and are more fuel efficient. We are making our fleet greener and cleaner.