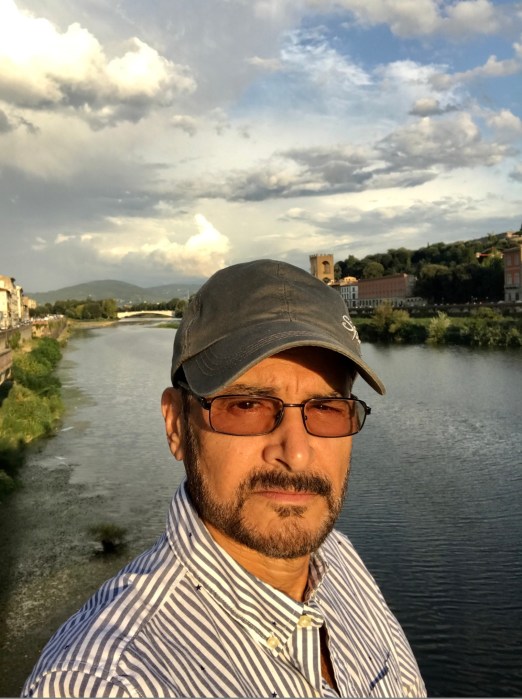

By Shoshanna McCollumWhen it comes to the preservation of cultural world treasures, few people are as driven or knowledgeable as Joshua David; co-founder of Friends of the High Line, now President and CEO of World Monuments Fund (WMF), and long-time resident of Cherry Grove. His mission to repurpose an abandoned rail system into a park took years to come to fruition. Today the High Line has transformed Manhattan’s lower west to the benefit of millions of New York City residents and visitors every year. This model project has earned him the Rockefeller Foundation Jane Jacobs Medal for New Ideas in 2010, and the National Building Museum’s Vincent Scully Prize in 2013. He now leads an international organization with WMF that has taken on Herculean preservation tasks that include Cambodia’s ancient temple of Phnom Bakheng, the Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as Historic Route 66 in the United States. FIN: As the Co-Founder of Friends of the High Line, what got you interested in such a massive preservation project?JD: I’ve lived in Chelsea since the late 1980s with my partner Stephen. I was a freelance writer, and in 1999 was assigned an article about the changes that were happening in Chelsea with the influx of art galleries. I started walking up and down every block for research, and that’s when I started really paying attention to the High Line for the first time. In poking around I found out that it was threatened with demolition. That seemed such an unfortunate outcome for a site that held such amazing opportunity – 22 blocks long, 30-feet in the air, and connecting three different neighborhoods:The Meatpacking District, West Chelsea, and the Hudson Yards. So I ended up going to a community board meeting, and by chance ended up sitting next to the only other person in the room who was possibly interested in making an effort it save it – Robert Hammond. Together, somewhat naively at the time, we started Friends of the High Line, without any real understanding of how complicated it was going to be. It was an unlikely and amazing start to something that was an unlikely and amazing project.FIN: From its founding as an idea in 1999 to opening of the park’s final phase in 2014, what gave you the motivation to keep on going?JD: I think we kept going because of our own passion for the project for – the structure itself, and what we though it could be. We were empowered by the passion that our neighbors in Chelsea and the Village, and across New York City, felt for the High Line. I think in the beginning we thought everyone would say that ‘you’re crazy’ and ignore us, but the outpouring of support from the early days is what really kept us going.FIN: How did this experience prepare you for what you are now doing with the World Monuments Fund?JD: My dad is a scientist, and he studied tropical diseases. As a family we traveled around the world a lot when I was growing up, while he was doing his research. We traveled to many of the kind of sites of the kind we now work in at the World Monuments Fund. I was deeply affected by going to those sites – places like the Temple of Karnack in Egypt, or Machu Picchu in Peru – places that you step into feel a tangible sense of the past and people who have gone before you. It was very impactful for me, and I think it had something to do with my starting the High Line. When Robert and I first stepped up there on top of the Highline for the first time, it had the feeling of an ancient site – you could feel this tangible sense of New York in another time; a New York of an industrial era where the west side was all about manufacturing and transportation. Experiencing the sites of heritage and history and architectural significance was important to me in my formative years, so when I was looking for something to do after the High Line, and I heard that the leadership position at the WMF was opening up, it interested me a lot.FIN: You assumed your role as President and CEO of WMF in November of 2015. What projects have you been involved with in your first six months?JD: We’re the leading international organization doing active conservation work at sites of architectural and artistic significance globally; and yet our size and our resources compared to the magnitude of the demand for our work, we are a small organization. Two of the things that are often the most pressing threats to sites of significance are the forces of nature and natural disaster, and man-induced conflict. When I was interviewing for WMF, about a year ago, a massive earthquake had struck Nepal. Along with their claiming thousands of lives, the earthquake also reduced a significant number of important historic heritage sites to rubble. It is something that I am particularly happy and proud about that one-year to the day after that earthquake, we were able to announce the reconstruction of an important temple in Nepal in partnership with the Katmandu Valley Preservation Trust and American Express. Responding to natural disasters is part of the DNA of WMF – we were founded in 1965, and one of our first projects was responding to the floods in Venice in 1966. Ever since then, we’ve been responding to natural disasters and the damage it causes to important sites, as well as conflict-related threats. It’s still too dangerous to go into Syria, where we’ve worked in the past, but it’s never too early to start planning to be able to go back there. And to that end, I started a new crisis response fund here at WMF. This will enable us to have a liquid pool of funds available to respond instantaneously when there’s an opportunity to help post-conflict or post-disaster.FIN: You are leading WMF into its next half-century, so what are some of your personal goals for it?JD: This is an organization that has the opportunity to grow ten-fold and still not see the end of meaningful work that we could do. I think it is very important to bring world resources to this effort. Part of that is communicating to a broader public about the importance of this kind of work. Conservation work at heritage sites can sound like an elite endeavor to some people, but when we go into these sites, we are actually engaging in the lives of local communities in very meaningful ways. We are sometimes training local residents in conservation techniques that give them valuable employment and build local capacity to steward their own heritage. We are also looking at places that are very much affected by changes in the geo-political environment. For instance, with the opening up of Cuba to the United States, it will create dramatic economic changes that in turn will have a huge pressure that will be felt by historic sites that have been protected partly by its isolation. Another area of real importance is urbanization. We are looking at a rapidly urbanizing planet, where the world’s cities are just growing by leaps and bounds, and again the economic pressures this puts on historic neighborhoods and structures is tremendous. Being able to look at conservation efforts not as a hindrance to economic growth, but as part of the growth of a vibrant and successful city, that’s something I think is very important to this organization and ties back to the High Line. Preservation is not necessarily about putting these places under glass like precious relics that couldn’t be touched, but rather harnessing the value of historic resources to create more socially vibrant and economically successful cities.FIN: I understand you are also a Cherry Grove resident. How long have you lived here?JD: We’ve been here since about 2004.FIN: Of all the places that you could have had a summer home, what was the appeal that made you settle on Fire Island?JD: When we first came to New York in the mid 1980s we visited Cherry Grove. It was during a terrible, early period of the AIDS crisis, when so many people were dying. We felt a pervasive sadness in the Grove at that time, and didn’t go back for a long time. Then in the late 1990’s a good friend of ours, Stephen Wilder, started inviting us out for weekends; we just fell in love with it. Fire Island’s beaches are some of the best in the world. When I was a magazine writer, I did a lot of travel writing, so have been to many beaches, but its hard to beat the beach on Fire Island! I also fell in love with the physical quality of the community of Cherry Grove – the modest size of many of the houses, and being able to walk on the boardwalks without any cars. There is also the amazing social element of the gay and lesbian community. It’s a very supportive community that does great things. The work Cherry Grove has done with its Dunes Fund really impressed me. Over the last few years I also became impressed with the efforts of how this very small community, without tons of money, managed to raise funds to rebuild their community house. The renovated first floor is opening this Memorial Day Weekend. This has been an amazing community effort that Cherry Grove should be very proud of.FIN: Not unlike the High Line there is a growing movement underway to declare Fire Island a World Heritage Site. What do you think of this idea?JD: I find it an intriguing idea. There are widely varying attitudes on Fire Island towards the rules that preserve the island’s architectural qualities and limited development. There are some who are frustrated by those limitations. I’m not – I come down on the side of the rules and the people who enforce them to keep Fire Island from over-developing. Anything that keeps Fire Island the place that it is; a very special and unique place that has long resisted overdevelopment, is for the better. It is really amazing that just a short distance from New York City you have a place that is still low-rise, with these long swaths of protected land in between the communities. This is a place that defeated plans for a massive road going through the middle of it. Certainly all of our communities have seen change, but it’s not nearly what you see in other places, where development has changed the nature of the place. That hasn’t happened on Fire Island. It is such a magic quality, and that is something we all should respect and treasure.Editor’s Note: To learn more about the High Line’s story, read “High Line: The Inside Story of New York City’s Park in the Sky,” by Joshua David and Robert Hammond – FSG Originals, 2011.