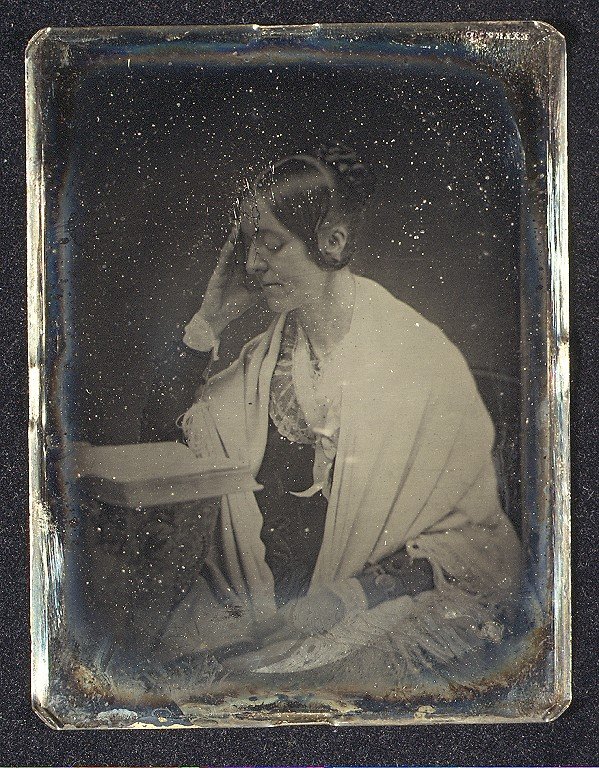

Southworth & Hawes, MMA Collection

Philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson described a person’s mortality as “not length of life, but depth of life.” This quote could easily eulogize the short life of Emerson’s friend Margaret Fuller. The early to mid-19th century United States was at the dawn of the first feminist movement. Fuller building on this spirit of shattering glass ceilings broke into a distinguished literary and media career.

Margaret Fuller was born May 23, 1810, in Massachusetts. Her father, Timothy Fuller, a congressman representing Massachusetts’s fourth congressional district, obtained an education for his daughter, which set her apart from many of her peers. Quickly moving up in New England’s intellectual circles, she befriended Ralph Waldo Emerson and became an editor for some of his literary works.

Gaining national attention for published works with Emerson, New York Tribune Publisher Horace Greeley hired Fuller as one of the first female foreign correspondents. She was sent to cover the war for Italian independence from Austria and France. Her salary from the Tribune was estimated to be $500 a year. Fuller befriended revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini during this time and helped attend to injured soldiers. While helping, she met Giovanni Ossoli. The two reported they were married, but historian and author Megan Marshall refuted this claim stating that no marriage certificate was ever found. The two had a son named Angelo, who was 20 months old when all three were scheduled to set sail for the United States in July of 1850.

Due to budget constraints, Fuller booked passage back to the United States on the “Elizabeth” freighter. Emerson offered to secure a ticket for her on a more comfortable passenger ship, but Fuller refused. The “Elizabeth” was filled with marble. Captain Seth Hasty was well-seasoned, but his crew needed to be more experienced. A smallpox outbreak plagued the crew and passengers within the voyage’s first weeks. The disease killed the captain and sickened Angelo. The first mate assumed command of the ship but his inexperience in navigation threw the ship off course. The first mate thought the Fire Island Lighthouse was the landmark of Cape May, New Jersey. On July 19, the “Elizabeth” found itself in the middle of a gale. Unfamiliar with the Fire Island coast and sandbars, the ship ran aground near Point O’ Woods. Due to its cargo weight, the ship started breaking apart in the surf. On the deck, Fuller, standing in a nightshirt, handed her son to a crew member who attempted to swim to shore with him. Once in the water, the two were pulled under by a current and never seen again. The mast gave way to a wave on deck, washing everyone off the deck, including Fuller and Ossoli. Many bodies were recovered in the coming days, but Fuller, Angelo, and Ossoli were not found. Wanting to recover Fuller’s personal effects and manuscript on her war correspondent work, Emerson sent his friend and fellow writer Henry David Thoreau to Fire Island. Thoreau found her desk and some papers, but her last piece of literary art was lost to the ocean’s depths.

Vintage postcard image of the Margaret Fuller memorial gazebo when it still in Point O’Woods, early 1900s.

Fuller and Ossoli’s bodies were only unaccounted for from the 10 killed aboard the “Elizabeth.” In the coming weeks, the sea would give up its dead, and the bodies of a woman and a man were discovered west of Point O’ Woods. Arthur Dominy, superintendent of the United States Life Saving Service, stated he gave the bodies to Captain Theodore Wicks of Bay Shore for burial. Once Wicks received the bodies, he contacted Greeley for identification. The bodies could not be fully identified, and Greeley refused to accept them. Wicks wanted the bodies off his sloop, waited until nightfall, and buried them on the beach at Coney Island. The exact location is lost to time.

In 1901, Point O’ Woods Improvement Society and resident Lillie Blake erected a memorial to Fuller, Ossoli and their son in the following decades. A gazebo was constructed on the dunes overlooking the sea and tethered inside a bronze plaque inscribed with a dedication to Fuller, but only a few years later, that memorial also would be be taken by the sea in a storm off the shores of Fire Island.