The sand that makes Fire Island is constantly shifting. An estimated 450,000,000 cubic yards of sediment joined multiple islands into a peninsula, which broke away from Long Island in a 1690 storm and became modern-day Fire Island. Longshore drift is sediment blowing from Montauk westwards, replenishing the beach from erosion and growing the island’s length. Within the last 200 years, this ongoing process expanded the six-mile stretch of western Fire Island, known as Robert Moses State Park. Controlling erosion and longshore drift to preserve a fragile ecosystem has been the most significant engineering challenge shrouded by human error.

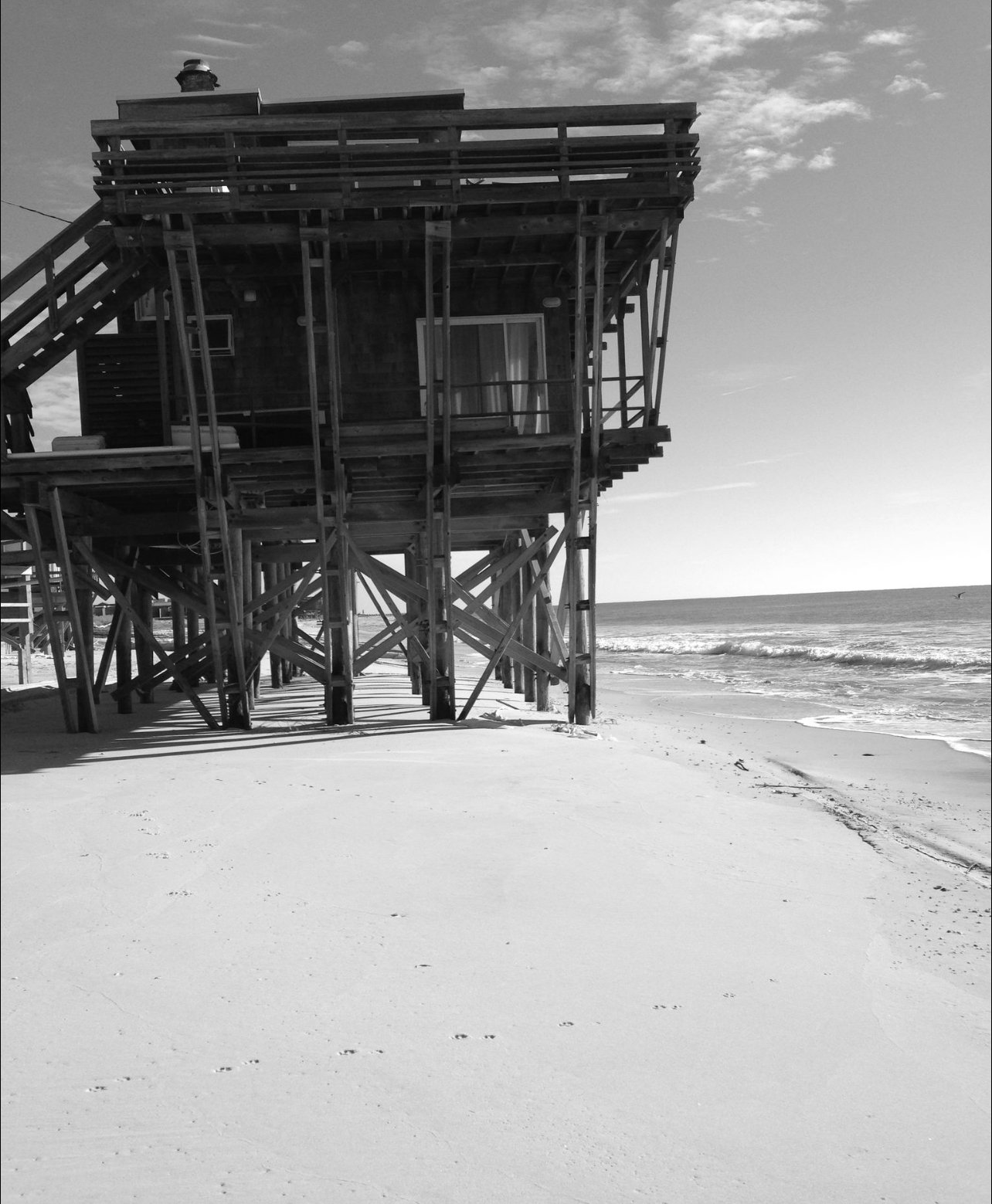

The oceanfront house that once existed at Robbins Rest was one of many structures along Fire Island’s shoreline that met the fate of condemnation after Superstorm Sandy.

As a result of the 1938 Hurricane, the Shinnecock Inlet was created, and the Moriches Inlet widened to 4,000 feet. The inlets would eventually fill in with the natural process of longshore drift. The Army Corps of Engineers constructed jetties and groin fields to reduce/block deposits from filling in the inlets by the mid-1950s. However, it restricted the natural process of replacing the hundreds of feet of eroded beach each year across Fire Island. In the aftermath of the 1962 Ash Wednesday Storm, a nor’easter that destroyed more than 100 homes, Robert Moses proposed his long-delayed Fire Island oceanfront highway plan.

“To connect Captree with Smiths Point would be an environmental disaster. If New Yorkers knew how much money is spent each year keeping Ocean Parkway from falling into the sea, it would probably soon be closed,” said Suffolk County’s Planning Board Director Lee Koppelman in a 1990 Newsday interview reflecting on Moses’s erosion plan.

By Sept. 11, 1964, Fire Island became a National Seashore, and the Fire Island Highway idea was dead. The problems created by the inlet stabilization measures were left to the federal government to partner up with local agencies to resolve the erosion. To replace the sediment, 500,000 cubic yards of native sand needed to be distributed along the coast west of Moriches Inlet. Further adding to the challenge required the maintenance of a 13- to 15-foot high, 30-mile long dune line. By the late 1970s, Fire Island faced the threat of projected sea-level rise and more rapid erosion.

To remedy the disrupted downward drift and erosion problem, the Army Corp of Engineers proposed a plan to intercept sand moving past the jetty into a reservoir basin. The sand would be removed by dredge, put in a second basin, and pumped to the beaches west of the Moriches Inlet. But before constructing a reservoir basin, the Corp would build an additional jetty from Westhampton to Moriches Inlet.

This plan came with criticism due to the tens of millions of dollars in construction costs and the central argument that jetty construction along the South Shore created the initial problem of Fire Island erosion.

In a public statement, Suffolk County Executive John Klein remarked, “This plan is hand-wrestling with God; it robs Peter to pay Paul with the groins catching sand moving in the ocean’s westward along the south shore, but robbing it from homes farther down the coast.” Representatives from Congressional budget offices have debated that they are funding the protection of “secondary summer homes.”

Despite the outcry over the effectiveness and cost of the plan, the jetties were constructed.

By 1989, erosion became a dire problem for Fire Island, causing the Army Corp of Engineers to take over the complete maintenance of the jetties and the groin field, giving the federal agency jurisdiction over an 83-mile stretch of the barrier island. As one 1990 Newsday editorial read, “The government is competing with the Atlantic Ocean for real estate on the shifting sands of Fire Island.”

On Oct. 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy created storm surges as high as 17 feet. Over half of the beaches and dunes were washed away on Fire Island. The Corps estimated the cost of a complete restoration was $170 million and required razing of 41 homes. But with all the new safeguards for beach and dune restoration, human error cannot be out engineered. The estimated 5,000 homes traversing Fire Island that face challenges from eastern groin fields and jetties wait to witness the next nor’easter or hurricane.