Maurice Sendak is the author of the 1964 Caldecott Award winning children’s book “Where the Wild Things Are.” The book remains number three on the top 10 bestselling children’s books of all time.1 You may have read it yourself. And while not often documented, Sendak also spent time on Fire Island. Background: The basics of Sendak’s life are well documented. He was born in Brooklyn in 1928, to Polish, Jewish immigrant parents, the youngest of three siblings. He was a sickly child, exposed early in life to the concept of mortality by deaths of family members during the Holocaust. Many of his books contain tracings of fences and towers and walls of concentration camps. At the age of 12 he saw Walt Disney’s “Fantasia” and decided to become an illustrator. In fact, Sendak so loved Disney that he has the second most extensive collection of Walt Disney memorabilia, second only to Walt’s own daughter. Upon graduation from the New York Art Students League he worked as a window dresser in the famous children’s toy store FAO Schwartz, but soon obtained commissions to illustrate Marcel Ayme’s “The Wonderful Farm” and Ruth Krauss’s “A Hole is to Dig.” He was on his way. The first book both written and illustrated by Sendak was “Kenny’s Window” (1956), followed by his four-volume “Nutshell Library” (1962). Perhaps his most ambitious endeavor was his trilogy based on the psychological development of children. First he wrote “Where the Wild Things Are” (1963) aimed at pre-school kids. Then came “In the Night Kitchen” (1970) for toddlers, and, finally, “Outside over There” (1981) for pre-adolescents. “In the Night Kitchen” was number 24 on the 100 Most Frequently Banned/Challenged Books of 2000-2009 for its depictions of a boy about 3 years old cavorting about naked. For a perspective, the Harry Potter books rank number one on that same list. In all, Sendak produced over 50 books, including illustrating “The Velveteen Rabbit.” In 1975, he expanded his horizons into television by writing and directing an animated special titled “Really Rosie.” He collaborated with Carole King to turn it into a musical play in 1978. With seemingly unlimited talent, Sendak also had a successful career as a stage designer for operas by Mozart, Prokofiev, and Ravel. He even staged Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker.”

Background: The basics of Sendak’s life are well documented. He was born in Brooklyn in 1928, to Polish, Jewish immigrant parents, the youngest of three siblings. He was a sickly child, exposed early in life to the concept of mortality by deaths of family members during the Holocaust. Many of his books contain tracings of fences and towers and walls of concentration camps. At the age of 12 he saw Walt Disney’s “Fantasia” and decided to become an illustrator. In fact, Sendak so loved Disney that he has the second most extensive collection of Walt Disney memorabilia, second only to Walt’s own daughter. Upon graduation from the New York Art Students League he worked as a window dresser in the famous children’s toy store FAO Schwartz, but soon obtained commissions to illustrate Marcel Ayme’s “The Wonderful Farm” and Ruth Krauss’s “A Hole is to Dig.” He was on his way. The first book both written and illustrated by Sendak was “Kenny’s Window” (1956), followed by his four-volume “Nutshell Library” (1962). Perhaps his most ambitious endeavor was his trilogy based on the psychological development of children. First he wrote “Where the Wild Things Are” (1963) aimed at pre-school kids. Then came “In the Night Kitchen” (1970) for toddlers, and, finally, “Outside over There” (1981) for pre-adolescents. “In the Night Kitchen” was number 24 on the 100 Most Frequently Banned/Challenged Books of 2000-2009 for its depictions of a boy about 3 years old cavorting about naked. For a perspective, the Harry Potter books rank number one on that same list. In all, Sendak produced over 50 books, including illustrating “The Velveteen Rabbit.” In 1975, he expanded his horizons into television by writing and directing an animated special titled “Really Rosie.” He collaborated with Carole King to turn it into a musical play in 1978. With seemingly unlimited talent, Sendak also had a successful career as a stage designer for operas by Mozart, Prokofiev, and Ravel. He even staged Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker.” Sendak and Fire Island: Sendak took a house on Fire Island with his companion/ lover Eugene Glynn in the early 1960s, and wrote “Where the Wild Things Are” (WTWTA) while living on Beachwold Avenue (also known as “B Street”) in Seaview. His neighbors, and fellow bon vivants, were Amos and Marcia Vogel, as well as Nat and Margo Hentoff. “They often met on the beach, where Sendak would sit for hours sketching,” recalls the Vogel’s son, Loring, who still comes out to Seaview regularly. The young Loring Vogel was the protagonist of a book collaboration, which was authored Loring’s father and illustrated by Sendak, entitled “How Little Lori Visited Times Square.” Copies of the book can still be purchased to this day. Sendak was a humanist, ribald while also conservative with a European sensibility. He wore a suit and tie even while championing the pleasure principle, the gratification of needs. Amos Vogel was the founder of the NYC avant-garde Cinema 16, famous for introducing new films by up-and-coming directors such as Roman Polanski, John Cassavetes, and Alan Resnais, among others. Nat Hentoff was a columnist for The Village Voice from 1958-2009, as well as a staff writer for The New Yorker. These three couples called themselves the “Nintimates,” hedonists of the early ‘60s, known for their love of freedom, fun and laughter. Sendak and Work: From journeyman to consummate artist, Sendak took great pains with each of his works. Originally, WTWTA was entitled “Where the Wild Horses Are.” The problem was that Sendak could not draw horses. His editor, Ursula Nordstrom, asked him in “acid tones” what could he draw. His response was “things,” so “things” it became. Sendak did not consider his books to be children’s books. In a piece in The New Yorker he stated, “Kid’s books…Grownup books… That’s just marketing. Books are Books.” He married the relationship between illustrations and words thusly: “Words are left out – but the picture says it. Pictures are left out – but the word says it.” His illustrations, he said, are “all a kind of caricatures of me. They look as if they’d been hit on the head, and hit so hard they weren’t going to grow anymore … I am trying to draw the way children feel – or, rather, the way I imagine they feel. It’s the way I know I felt as a child.” He loved music and was obsessed with Mozart. “I wanted at all costs to avoid the serious pitfall of illustrating with pictures what the author had already … illustrated with words. I hoped, rather, to let the story speak for itself, with my pictures as a kind of background music – music in the right style and always in tune with the words.” True to his word, he drew and painted to music, trying always to find the right piece to fit the mood of his work. And he drew and listened, listened and drew, drew and listened.

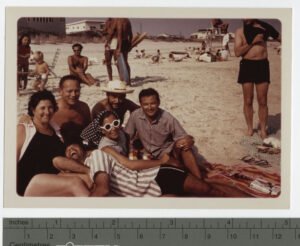

Sendak and Fire Island: Sendak took a house on Fire Island with his companion/ lover Eugene Glynn in the early 1960s, and wrote “Where the Wild Things Are” (WTWTA) while living on Beachwold Avenue (also known as “B Street”) in Seaview. His neighbors, and fellow bon vivants, were Amos and Marcia Vogel, as well as Nat and Margo Hentoff. “They often met on the beach, where Sendak would sit for hours sketching,” recalls the Vogel’s son, Loring, who still comes out to Seaview regularly. The young Loring Vogel was the protagonist of a book collaboration, which was authored Loring’s father and illustrated by Sendak, entitled “How Little Lori Visited Times Square.” Copies of the book can still be purchased to this day. Sendak was a humanist, ribald while also conservative with a European sensibility. He wore a suit and tie even while championing the pleasure principle, the gratification of needs. Amos Vogel was the founder of the NYC avant-garde Cinema 16, famous for introducing new films by up-and-coming directors such as Roman Polanski, John Cassavetes, and Alan Resnais, among others. Nat Hentoff was a columnist for The Village Voice from 1958-2009, as well as a staff writer for The New Yorker. These three couples called themselves the “Nintimates,” hedonists of the early ‘60s, known for their love of freedom, fun and laughter. Sendak and Work: From journeyman to consummate artist, Sendak took great pains with each of his works. Originally, WTWTA was entitled “Where the Wild Horses Are.” The problem was that Sendak could not draw horses. His editor, Ursula Nordstrom, asked him in “acid tones” what could he draw. His response was “things,” so “things” it became. Sendak did not consider his books to be children’s books. In a piece in The New Yorker he stated, “Kid’s books…Grownup books… That’s just marketing. Books are Books.” He married the relationship between illustrations and words thusly: “Words are left out – but the picture says it. Pictures are left out – but the word says it.” His illustrations, he said, are “all a kind of caricatures of me. They look as if they’d been hit on the head, and hit so hard they weren’t going to grow anymore … I am trying to draw the way children feel – or, rather, the way I imagine they feel. It’s the way I know I felt as a child.” He loved music and was obsessed with Mozart. “I wanted at all costs to avoid the serious pitfall of illustrating with pictures what the author had already … illustrated with words. I hoped, rather, to let the story speak for itself, with my pictures as a kind of background music – music in the right style and always in tune with the words.” True to his word, he drew and painted to music, trying always to find the right piece to fit the mood of his work. And he drew and listened, listened and drew, drew and listened. But he did not write for children per se. “I really do these books for myself. It’s something I have to do, find it’s the only thing I want to do. Reaching the kids is important, but secondary. First, always, I have to reach and keep hold of the child in me.” Sendak and Children: Maurice loved children. His editor Nordstrom once said, “[S]omehow Maurice has retained a direct line to his own childhood.” Maurice was their champion, dealing directly and honestly with them. He protected the sanctity of children’s feelings – even though he remembered his own childhood with some trepidation. Some characters in WTWTA are representations of his relatives with their yellow teeth and wild hair who came to visit, pulling at him, pinching him and eating all his food. “In reality, childhood is deep and rich. It’s vital, mysterious, and profound. I remember my own childhood vividly … I knew terrible things, but I knew I mustn’t let adults know I knew … it would scare them.”And: “You can’t protect kids. They know everything.”And: “My childhood self … as if it were all quaint and succulent like Peter Pan. Childhood is cannibals and psychotics vomiting in your mouth.” While many adults found his stories and pictures of beasts frightening, the children had no such fears. Somehow Sendak tamed these “wild things.” A 7-year-old boy once wrote him a letter in which he wrote, “How much does it cost to get to where the wild things are? If it is not too expensive my sister and I want to spend the summer there. Please answer soon.” In spite of the grotesque, he touched a nerve in children. “A little boy sent me a charming card with a little drawing on it. I loved it. I answer all my children’s letters – sometimes very hastily – but this one I lingered over. I sent him a card and I drew a picture of a Wild Thing on it. I wrote, ‘Dear Jim: I loved your card.’ Then I got a letter back from his mother and she said: ‘Jim loved your card so much he ate it.’ That to me was one of the highest compliments I’ve ever received. He didn’t care that it was an original Maurice Sendak drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it.” Sendak on Death: Although Sendak was an atheist and did not believe in an afterlife, he fully believed that he would see his dead brother again. He also sighed that a belief in God “must have made life much easier. It’s harder for us non-believers.” “I have nothing now but praise for my life. I’m not unhappy. I cry a lot because I miss people. They die and I can’t stop them. They leave me and I love them more … What I dread is the isolation … There are so many beautiful things in the world which I will have to leave when I die, but I’m ready, I’m ready, I’m ready.” “It is a blessing to get old, to find the time to read the books, to listen to the music … I will cry my way all the way to the grave … Live your life. Live your life. Live your life.” Sendak died in Danbury, Connecticut, on May 8, 2012, shortly before his 84th birthday. His body was cremated.

But he did not write for children per se. “I really do these books for myself. It’s something I have to do, find it’s the only thing I want to do. Reaching the kids is important, but secondary. First, always, I have to reach and keep hold of the child in me.” Sendak and Children: Maurice loved children. His editor Nordstrom once said, “[S]omehow Maurice has retained a direct line to his own childhood.” Maurice was their champion, dealing directly and honestly with them. He protected the sanctity of children’s feelings – even though he remembered his own childhood with some trepidation. Some characters in WTWTA are representations of his relatives with their yellow teeth and wild hair who came to visit, pulling at him, pinching him and eating all his food. “In reality, childhood is deep and rich. It’s vital, mysterious, and profound. I remember my own childhood vividly … I knew terrible things, but I knew I mustn’t let adults know I knew … it would scare them.”And: “You can’t protect kids. They know everything.”And: “My childhood self … as if it were all quaint and succulent like Peter Pan. Childhood is cannibals and psychotics vomiting in your mouth.” While many adults found his stories and pictures of beasts frightening, the children had no such fears. Somehow Sendak tamed these “wild things.” A 7-year-old boy once wrote him a letter in which he wrote, “How much does it cost to get to where the wild things are? If it is not too expensive my sister and I want to spend the summer there. Please answer soon.” In spite of the grotesque, he touched a nerve in children. “A little boy sent me a charming card with a little drawing on it. I loved it. I answer all my children’s letters – sometimes very hastily – but this one I lingered over. I sent him a card and I drew a picture of a Wild Thing on it. I wrote, ‘Dear Jim: I loved your card.’ Then I got a letter back from his mother and she said: ‘Jim loved your card so much he ate it.’ That to me was one of the highest compliments I’ve ever received. He didn’t care that it was an original Maurice Sendak drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it.” Sendak on Death: Although Sendak was an atheist and did not believe in an afterlife, he fully believed that he would see his dead brother again. He also sighed that a belief in God “must have made life much easier. It’s harder for us non-believers.” “I have nothing now but praise for my life. I’m not unhappy. I cry a lot because I miss people. They die and I can’t stop them. They leave me and I love them more … What I dread is the isolation … There are so many beautiful things in the world which I will have to leave when I die, but I’m ready, I’m ready, I’m ready.” “It is a blessing to get old, to find the time to read the books, to listen to the music … I will cry my way all the way to the grave … Live your life. Live your life. Live your life.” Sendak died in Danbury, Connecticut, on May 8, 2012, shortly before his 84th birthday. His body was cremated.