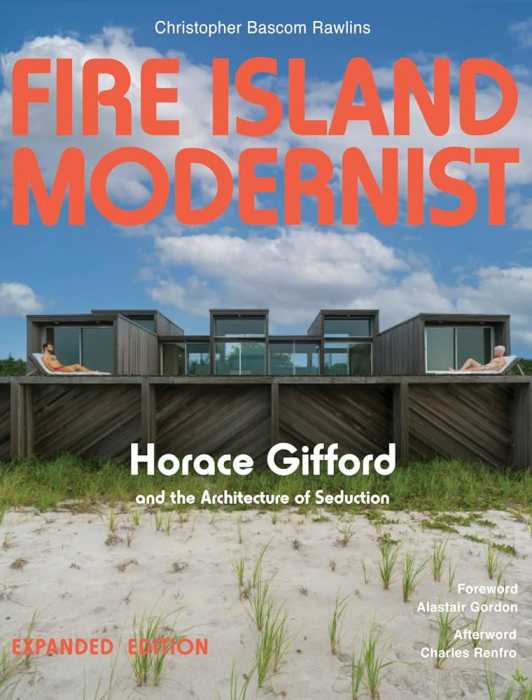

Fire Island Modernist: Horace Gifford and the Architecture of Seduction, Christopher Bascom Rawlins‘ seminal work about architectural visionary Horace Gifford, first released in 2013, has been reissued and expanded, with new houses and photos, and an Afterword by noted architect Charles Renfro. Think Beach houses in blocky, angled cedar wood; glass doors on parallel walls that merge living spaces with nature.

He was only 28, but “When he drove his first piling into the lightly settled sands of Fire Island, his work already possessed clarity and conviction.” Brimming with confidence, “Horace would stroll to meetings along the beach, wearing a Speedo and carrying an attaché case. It was quite a sight.”

Openly gay in college—no small feat in the ‘50s—he said of himself, “There are two things you should know about me. I’m gay and I’m manic depressive.” And in 1965, upon completing a new home for a client, “You will now have twenty closets to come out of.”

Chapter headings such as “Boys in the Sand” and “Form Follows Foreplay” suit Gifford’s bold and provocative personality. And yet, he couldn’t apply for an architecture license; he’d been arrested in the dunes for immoral behavior. (Even on free-thinking Fire Island, a refuge for gays, there were limits in the ‘60s.) However, that didn’t stop the young creative from becoming a renowned and sought-after architect, who, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, put his name on 63 Modernist houses across the Island.

Open floor plans, flat roofs, function and simplicity, and a less-is-more approach to home design are the tenets of the Modernist style that Gifford took to the nth degree in his own home—he was not a man of moderation.

Its structure “formed a pinwheel of shed-roofed towers around a living area that exploded into voyeuristic stages for living… glass doors [that] opened wide to create a breezeway through which birds flew, achieving a remarkable tension between… the flat-roofed public spaces and the high-waisted sentinels housing the bedrooms, bathroom and kitchen. With this home, Gifford perfected the transition from nature to architecture,” writes Christopher Rawlins, a historian, award-winning architect, and accomplished writer.

Photos of his sketches—meticulous line drawings and models of his work—detail his ideas taking shape, ending with beautifully lit shots of the finished homes.

“He pursued the mysteries of light, shadow and space as a poet might,” Alastair Gordon writes in the Foreword, highlighting his daring creativity.

Rawlins covers Gifford’s early life in Florida, his education and mentors, as well as his professional failures and successes. Lively anecdotes uncover a ménage-à-trois with his first New York client and the latter’s partner, which lasted several years. “Don’t mix business with pleasure” had no place on Gifford’s drawing board.

A champion of the master’s work, Rawlins—As far as the “not insignificant matter of learning how to write,” Rawlins touches on. From where this reviewer sits and reads, his easy, often lyrical way with words indicates he has nothing to worry about.

It is a large, handsome book with a strong visual impact and is full of high-quality photos. Fire Island Modernist has all the markings of a “coffee table” book, something you might pick up and peruse at leisure. But it’s a good read too, and there’s a story in Rawlin’s engaging narrative that blends architectural and cultural history, and turns back to when the Surf Hotel opened in 1885. Regarding the more recent past, the author offers a candid look at gay life and culture of the ‘60s and ‘70s, on and off Fire Island.

In closing, Rawlins addresses Gifford’s houses as “honest and simple… unadorned elegant boxes that commune and conspire with nature, allowing the exterior setting to become the interior adornment. They enlist nature as a theatrical partner; flowers come and go, tides rise and fall, all framed or revealed in the simple gesture of his houses.”

Putting this tome together took extensive research and money, and then, to have to break through “a challenging publishing environment…. Alas,” the author comments, “raising the dead is not for the faint of heart or the slim of wallet.”

Rawlins is the principal of Rawlins Design and a cofounder of Pines Modern, a nonprofit celebrating the mid-century architecture of the Pines. For more information, visit pinesmodern.org.