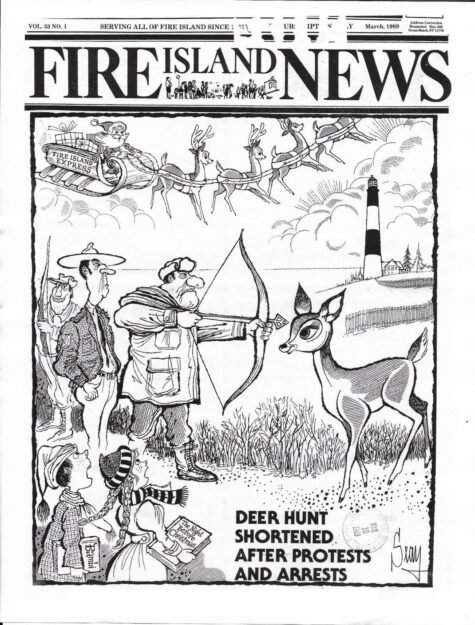

The Fire Island News (FIN), once a weekly, was delivered to the doorsteps of those who subscribed for 15 cents an issue. Readers would find their copy of the news at their doorstep – and its first impression – a collection of diverse characters established by fine lines, underneath the iconic newspaper logo. And in the bottom corner, a boxy signature that reads “Seay.”William “Bill” Seay was the cover artist, cartoonist and art director for FIN for approximately two decades. His work decorated the front cover, centerfold, and most, if not all, breaking news, to provide comic relief and artistic critique.Born in Havana, Illinois, Seay began drawing front page editorial cartoons for his local daily newspaper while he was in high school. The early stages of his career led him to Meyer Both Studios in Chicago as cartoonist and art director, where he dabbled with Hugh Hefner’s Playboy, and later, to New York where he served as art director for the JCPenney Catalog and as an illustrator at some upscale magazines.The latter end of his career led him to Fire Island in Cherry Grove, where he was introduced to longtime executive editor of the Fire Island News, Ildiko Trien.“A man I used to know who we’d call Sir William came up to me in Cherry Grove one day, and said there was somebody he’d like me to meet,” Ildiko, who was married to Jay Trien, founder of FIN, said. “It was Bill Seay … he said he’d like to work for me … the rest is history.”Ildiko said she would join Seay and his wife, Mimi Jelliffe, at their Huntington home, tucked away in a cul-de-sac, during the winter for 10 days at a time. The three of them would devote their time to drafting and finalizing artwork to embellish 60 issues, including six special winter editions to provide readers “just enough before there was frost on the dunes.”One winter edition cover from March 1989 made rounds back in 2019 in a post-production addition circulated by the Fire Island Wildlife Foundation, where Seay’s cover illustrates a desolate winter Fire Island seashore beside the Fire Island Lighthouse. One eye of the reader is drawn to three men, one with an arrow drawn to a deer’s head, and the other to the two children who lay beneath them, astonished in their

The Fire Island News (FIN), once a weekly, was delivered to the doorsteps of those who subscribed for 15 cents an issue. Readers would find their copy of the news at their doorstep – and its first impression – a collection of diverse characters established by fine lines, underneath the iconic newspaper logo. And in the bottom corner, a boxy signature that reads “Seay.”William “Bill” Seay was the cover artist, cartoonist and art director for FIN for approximately two decades. His work decorated the front cover, centerfold, and most, if not all, breaking news, to provide comic relief and artistic critique.Born in Havana, Illinois, Seay began drawing front page editorial cartoons for his local daily newspaper while he was in high school. The early stages of his career led him to Meyer Both Studios in Chicago as cartoonist and art director, where he dabbled with Hugh Hefner’s Playboy, and later, to New York where he served as art director for the JCPenney Catalog and as an illustrator at some upscale magazines.The latter end of his career led him to Fire Island in Cherry Grove, where he was introduced to longtime executive editor of the Fire Island News, Ildiko Trien.“A man I used to know who we’d call Sir William came up to me in Cherry Grove one day, and said there was somebody he’d like me to meet,” Ildiko, who was married to Jay Trien, founder of FIN, said. “It was Bill Seay … he said he’d like to work for me … the rest is history.”Ildiko said she would join Seay and his wife, Mimi Jelliffe, at their Huntington home, tucked away in a cul-de-sac, during the winter for 10 days at a time. The three of them would devote their time to drafting and finalizing artwork to embellish 60 issues, including six special winter editions to provide readers “just enough before there was frost on the dunes.”One winter edition cover from March 1989 made rounds back in 2019 in a post-production addition circulated by the Fire Island Wildlife Foundation, where Seay’s cover illustrates a desolate winter Fire Island seashore beside the Fire Island Lighthouse. One eye of the reader is drawn to three men, one with an arrow drawn to a deer’s head, and the other to the two children who lay beneath them, astonished in their winter gear.All of the outrage, protests and even arrests over the “scientific” deer hunt was captured in his black and white cover illustration. Addressed in depth, the special winter edition was printed by the thousands and mailed to Fire Island and mainland residents.“I needed a great cartoonist to illustrate what was happening at the time in a sense that people could understand aside from the print itself … in a socially communicative sense. Bill could do that in a manner that matched the essence of Fire Island … because he understood it,” Ildiko said. According to the Triens, Bill drafted an edition of a series called “Lighthouse Mouse” to appear in almost every issue.Seay was not only a member but the chapter president of the Long Island branch of the distinguished National Cartoonist Society – the largest professional organization for cartoonists. Founded in 1947, the organization is rooted in their members’ commonality to artistically entertain, according to their website.The Berndt Toast Gang, coined to describe the Long Island Chapter after the passing of Walter Berndt and his iconic comic in the early ’20s for the Chicago Tribune, “Smitty,” was one of which Seay was a keystone member according to those sought for comment.An article published by The New York Times in 2001 describes the New York cartoonist atmosphere, where Seay said, to him, creating a comic strip was like writing a novel in four panels. The last “panel” of Seay’s life ended the same year as that article’s publication; Seay took his own life only days after Mimi was laid to rest.

winter gear.All of the outrage, protests and even arrests over the “scientific” deer hunt was captured in his black and white cover illustration. Addressed in depth, the special winter edition was printed by the thousands and mailed to Fire Island and mainland residents.“I needed a great cartoonist to illustrate what was happening at the time in a sense that people could understand aside from the print itself … in a socially communicative sense. Bill could do that in a manner that matched the essence of Fire Island … because he understood it,” Ildiko said. According to the Triens, Bill drafted an edition of a series called “Lighthouse Mouse” to appear in almost every issue.Seay was not only a member but the chapter president of the Long Island branch of the distinguished National Cartoonist Society – the largest professional organization for cartoonists. Founded in 1947, the organization is rooted in their members’ commonality to artistically entertain, according to their website.The Berndt Toast Gang, coined to describe the Long Island Chapter after the passing of Walter Berndt and his iconic comic in the early ’20s for the Chicago Tribune, “Smitty,” was one of which Seay was a keystone member according to those sought for comment.An article published by The New York Times in 2001 describes the New York cartoonist atmosphere, where Seay said, to him, creating a comic strip was like writing a novel in four panels. The last “panel” of Seay’s life ended the same year as that article’s publication; Seay took his own life only days after Mimi was laid to rest. “A lot of the wives at home were glad to get rid of their cartoonist husbands who worked from home … but Mimi, she was always with Bill,” said Bunny Hoest, 88, from Huntington and a Newsday cartoonist herself. “They still wanted to be together after being together at home … Mimi and Bill were a unit.”Also a member of the Long Island Cartoonist Society, 59-year-old Mike Lynch described the Seay’s as “welcoming people” regardless of who they met. “Bill was very supportive of me,” Lynch said. “You meet people of an older age when you’re young sometimes and just know that if you were the same age, you’d be best pals forever … that was Bill. He was the nicest fellow.”That same 2001 New York Times article quotes Seay, where he describes his cartoonist technique to begin with a great last line. A man who described his creative process as one traveling backwards, Seay’s social and political satire discriminated against no one and welcomed just about every one.

“A lot of the wives at home were glad to get rid of their cartoonist husbands who worked from home … but Mimi, she was always with Bill,” said Bunny Hoest, 88, from Huntington and a Newsday cartoonist herself. “They still wanted to be together after being together at home … Mimi and Bill were a unit.”Also a member of the Long Island Cartoonist Society, 59-year-old Mike Lynch described the Seay’s as “welcoming people” regardless of who they met. “Bill was very supportive of me,” Lynch said. “You meet people of an older age when you’re young sometimes and just know that if you were the same age, you’d be best pals forever … that was Bill. He was the nicest fellow.”That same 2001 New York Times article quotes Seay, where he describes his cartoonist technique to begin with a great last line. A man who described his creative process as one traveling backwards, Seay’s social and political satire discriminated against no one and welcomed just about every one.