A Moment In History Together

By Danielle Lipiec The story of Ruby Bridges, the young girl who broke boundaries as the first African-American child to attend an all-white school, is one known to many. The account of her brave march to her first day of integrated school in 1960’s Louisiana can be found in history books, and our collective memories. There for it all was Long Island-born U.S. Marshal Gerald O’Rourke. His part in this pivotal moment in history brings the story almost 1,500 miles up to Ocean Beach, to the historical archives of Fire Island.O’Rourke began his career with the United States government as a criminal investigator with the Maryland State Police, and a deputy U.S. marshal with the U.S. Department of Justice. “My father was very young when he took the U.S. marshal position,” said O’Rourke’s son, Sean O’Rourke. “A lot of people considered him a boy wonder, or not old enough for the position. He proved them wrong.”Starting as a bodyguard for Robert F. Kennedy, O’Rourke gradually maneuvered his way to the field work he continuously sought early in his career. After some time, O’Rourke found it in himself to express to Kennedy his displeasure with his line of work at the time. “He told Bobby that he didn’t want to be ‘the president’s younger brother’s babysitter anymore,” Sean said. Kennedy asked him what he wanted to do, and soon after, O’Rourke would be in the southern states, enforcing federal school integration orders in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. “That is how he wound up in New Orleans with Ruby Bridges,” Sean said.A November morning in 1960, in front of William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, Louisiana, entailed O’Rourke and three other U.S. marshals escorting Bridges to her first day at the all-white school. Even with a potent essence of racism, separated facilities on every corner, and many controversial opinions on the matter of racial integration, O’Rourke expressed to his son an opinion decades ahead of its time.“The colored people I arrest are not bad people – they just don’t yet have the same opportunities that Caucasians have,” Sean said, quoting his father.

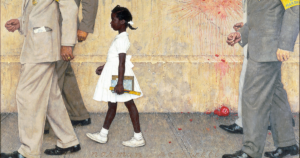

The story of Ruby Bridges, the young girl who broke boundaries as the first African-American child to attend an all-white school, is one known to many. The account of her brave march to her first day of integrated school in 1960’s Louisiana can be found in history books, and our collective memories. There for it all was Long Island-born U.S. Marshal Gerald O’Rourke. His part in this pivotal moment in history brings the story almost 1,500 miles up to Ocean Beach, to the historical archives of Fire Island.O’Rourke began his career with the United States government as a criminal investigator with the Maryland State Police, and a deputy U.S. marshal with the U.S. Department of Justice. “My father was very young when he took the U.S. marshal position,” said O’Rourke’s son, Sean O’Rourke. “A lot of people considered him a boy wonder, or not old enough for the position. He proved them wrong.”Starting as a bodyguard for Robert F. Kennedy, O’Rourke gradually maneuvered his way to the field work he continuously sought early in his career. After some time, O’Rourke found it in himself to express to Kennedy his displeasure with his line of work at the time. “He told Bobby that he didn’t want to be ‘the president’s younger brother’s babysitter anymore,” Sean said. Kennedy asked him what he wanted to do, and soon after, O’Rourke would be in the southern states, enforcing federal school integration orders in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. “That is how he wound up in New Orleans with Ruby Bridges,” Sean said.A November morning in 1960, in front of William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, Louisiana, entailed O’Rourke and three other U.S. marshals escorting Bridges to her first day at the all-white school. Even with a potent essence of racism, separated facilities on every corner, and many controversial opinions on the matter of racial integration, O’Rourke expressed to his son an opinion decades ahead of its time.“The colored people I arrest are not bad people – they just don’t yet have the same opportunities that Caucasians have,” Sean said, quoting his father. This moment that O’Rourke took part in would come with a photo to prove it, and a famous painting by Norman Rockwell, titled “The Problem We All Live With,” to be displayed in the Rockwell Museum. A copy also can be found in the U.S. Marshal’s Museum in Arkansas.“All through my childhood my father had a lithograph of the painting hanging on the wall of his office,” Sean said. “He used to tell us, ‘I’m famous,’ and point to the picture.”As a hospital corpsman in the Navy during the Korean War, youngest lead criminal investigator in Maryland State Police history, U.S. marshal, independent security management consultant, founding member of the Maryland State Police Alumni Association, adjunct professor at John Jay College and father to seven children, O’Rourke did not live a dull life.“He was very humble about all of his accomplishments,” Sean said. And with six of his seven children being Long Island-born along with O’Rourke himself, it’s difficult to separate his story from the island. “He loved Fire Island, he came here very frequently with his boat. Now my brother and I always rent out here,” Sean said.At the age of 63 when this article went to print, Ruby Bridges Hall still lives in New Orleans, and presently chairs the Ruby Bridges Foundation, founded in 1999. Gerald O’Rourke would pass away in 2006. Sean’s vivid description keeps his father’s humorous spirit alive, and paints the clearest picture of who Gerald O’Rourke was, not only as a government employee or father, but as an individual. His lifetime of government work and assistance during southern desegregation efforts lends a page to U.S. and Fire Island history books alike.

This moment that O’Rourke took part in would come with a photo to prove it, and a famous painting by Norman Rockwell, titled “The Problem We All Live With,” to be displayed in the Rockwell Museum. A copy also can be found in the U.S. Marshal’s Museum in Arkansas.“All through my childhood my father had a lithograph of the painting hanging on the wall of his office,” Sean said. “He used to tell us, ‘I’m famous,’ and point to the picture.”As a hospital corpsman in the Navy during the Korean War, youngest lead criminal investigator in Maryland State Police history, U.S. marshal, independent security management consultant, founding member of the Maryland State Police Alumni Association, adjunct professor at John Jay College and father to seven children, O’Rourke did not live a dull life.“He was very humble about all of his accomplishments,” Sean said. And with six of his seven children being Long Island-born along with O’Rourke himself, it’s difficult to separate his story from the island. “He loved Fire Island, he came here very frequently with his boat. Now my brother and I always rent out here,” Sean said.At the age of 63 when this article went to print, Ruby Bridges Hall still lives in New Orleans, and presently chairs the Ruby Bridges Foundation, founded in 1999. Gerald O’Rourke would pass away in 2006. Sean’s vivid description keeps his father’s humorous spirit alive, and paints the clearest picture of who Gerald O’Rourke was, not only as a government employee or father, but as an individual. His lifetime of government work and assistance during southern desegregation efforts lends a page to U.S. and Fire Island history books alike.