At the turn of the century, Bay Shore became a hotspot for some of the nation’s most successful business leaders. Maple Avenue, Ocean Avenue, and Shore Lane earned the nickname Millionaires’ Row by locals. The Havemeyer sugar family, Thomas Adams, founder of Adams Chewing Gum, and Detective Agency heir Robert A. Pinkerton all had homes along the canals of Bay Shore.

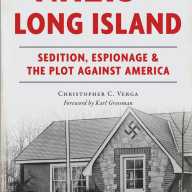

However, Bay Shore, unlike many other summer resort communities for the wealthy, did not hold hostile attitudes toward Jewish people or enforce real estate covenants that prevented selling homes to Jewish families. In the 1920s, Long Island had a Ku Klux Klan presence estimated at one in seven residents, but in Bay Shore, the Catholic community united against the Klan and kept them out of local influence. These factors made Bay Shore an attractive destination for upper-middle-class Jewish families, who would later establish a congregation.

The earliest records of the formation of a congregation date back to October 23, 1896, in The American Hebrew & Jewish Messenger, which stated: “The Jewish population of Bay Shore asked the Oakwood Cemetery Association to set apart some of their ground for the use of the Jews.”

The early records date back to January 1898, as reported in The American Hebrew, which noted that Gerson Bloch and Emanuel Underberger, President of the United Hebrew Benevolent Cemetery Association, established Bay Shore’s first Hebrew school. The first class consisted of nine students.

During the earliest development of Bay Shore’s Jewish community, Simon Rothchild and Edward Charles Blum, partners of the department store chain Abraham & Straus; Solomon Stein, founder of the wholesaler firm S. Stein & Co.; Noah Taussing, CEO of American Molasses Company; and the Oppenheimer family, who built a fortune in textiles (and later son Julius Robert Oppenheimer, who developed the atomic bomb), all built homes in Bay Shore. This who’s who of the Jewish community defined Bay Shore as a status symbol for success among New York’s Jewish population.

Bay Shore would not only attract the wealthiest Jewish families but also serve as a hub for activism within the New York Jewish community. After earning his PhD, a young Stephen Wise, who later became a prominent Reform Rabbi and a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), spent summers in Bay Shore. During these summers, Rabbi Wise took on the fight against political corruption, especially in Philadelphia. When criticized for not being a resident of Philadelphia, Wise responded with one of his most famous rebuttals, which outlined the moral responsibilities of citizens against the backdrop of Bay Shore.

“I hold that a citizen of the United States is neither a stranger nor a guest in any part of the land. We are citizens of the United States before citizens of Oregon [or any other state]. Therefore, the moral interests of Philadelphia are vital to me as those of New York.”

In 1918, the United Hebrew Congregation of Bay Shore was officially founded, and it opened its first synagogue at the old firehouse on Second Avenue. With the congregation’s establishment, Bay Shore drew influential national figures, including members of President Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet.

Published in May 1918, The American Hebrew & Jewish Messenger reported, “Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Baruch will summer at Bay Shore, where they have taken Charles Lanier Lawrence’s place, Montauk Farms for the season.”

Baruch, a well-known Wall Street investor, left his finance firm to become chairman of the War Industries Board in January 1918, eight months after the United States entered World War I.

During the summer of 1918, his leadership prevented backlogs in the USA military supply chains through innovative policies on wartime manufacturing and distribution. The outcome of his decisions, made while summering in Bay Shore, not only paved the way for a decisive American victory in World War I but was replicated for World War II, establishing the United States as a global power.

The merger of the United Hebrew Congregation and the Bay Shore chapter of the Brooklyn-based Jewish Alliance created the modern Jewish Centre of Bay Shore in the 1950s. The remnants of the resort-oriented economy and the community they built have faded into distant memory with the growth of post-war suburbia.