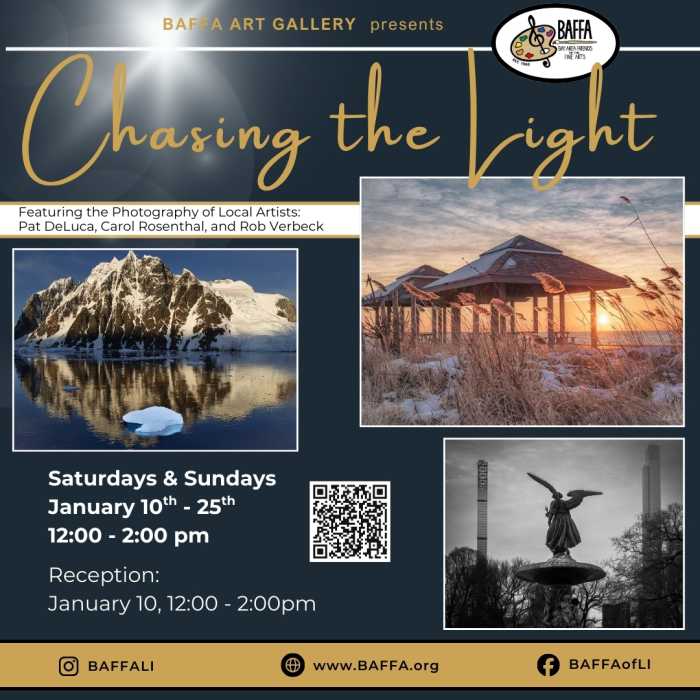

Now in its tenth year, BOFFO is a nonprofit arts community in the Pines, known for its residency program and annual performance festival. On July 13 and 14, a total of 10 performances centered around the theme of Dystopian Ecstasy unfolded across the beach, a house, and a helipad, curated by Sydney Fishman and Lucas Ondak.

BOFFO serves to elevate the work of queer artists working across media, generations, and practices, creating interdisciplinary dialogues that spark change and foster community. The festival showcases a range of performances and DJ sets, and has, in past years, featured renowned artists such as Cassils, Juliana Huxtable, and Jacolby Satterwhite.

The questions that took shape in my mind were: Is it possible to separate performance from spectacle? Does site-specific performance act as a counterpoint to the disembodied experience of an institutional exhibition? Can utopia be salvaged from its patriarchal-colonial origins, or is liberation to be found, instead, in reimagining and reclaiming dystopia?

The afternoon commenced with a spectacular feat of endurance by performance artist and choreographer Jas Lin. Stepping onto a treadmill facing the water, they began walking rhythmically, a microphone on the base of the machine magnifying their steps. Each footfall echoed behind the crowd clustered in the sand, emitted from a speaker further up the beach.

Eventually, Lin broke into a run—a steady jog at first, then a sprint. On the verge of flying off the back of the treadmill, they commanded the machine to slow its steady churn. Their steps became less mechanical, dancing as if pulling down the sky or exorcising the ingrained movements and embodied tyrannies from their body. Words intermingled periodically with amplified strides.

As the crowd fell silent, Lin fell to their knees, and their steps turned to a crawl; then they were in the sand, grasping the treadmill with striking tenderness. The machine became a body between their fingers.

Crawling the length of its belt, Lin unfurled their body through the front of the treadmill as if purged from its hold. I couldn’t help but think of Samara’s ghost oozing out of the TV in The Ring—perhaps fitting, given Lin’s embrace of the abject and the uncanny. The steady thuds faded into language: Every day I reach for the ocean and the ocean reaches back for me. The crowd rose and followed Lin as they slinked toward the water’s edge; I had the feeling they would have followed Lin into the sea. A remarkable stillness fell over the beach as they lay coiled serpentine in the tide.

Nile Harris directs works of live art that meld merciless hilarity and casual tragedy. Drawing together elements of improv, dance, and satire, his work raises (often explicitly posed) questions about race, American culture, queer communities, and their uneasy intersections.

Harris’s festival constituted a meta enactment of a delightfully messy Fire Island summer. Produced in collaboration with artist, writer, and performer Dyer Rhoads, the participatory piece drew audience members into a multilayered play, the resulting cacophony of voices and gestures eliciting laughter and eye-rolls of recognition from the crowd gathered at its edges. As Harris and others read snippets of overheard Pines exchanges interspersed with miscellaneous ponderings, volunteers tossed a beach ball, held up a painted sun, and strutted up and down the sand as if on a runway.

The resulting act was as much summer camp as Sontag. The failed seriousness of art imitating life imitating art let the self-referential logic of artmaking fall away (or perhaps more accurately, fall apart); it’s hard not to lose the plot with quasi-literary nonsense and self-serious chatter ping-ponging back and forth overhead.

As laughter rippled out over the water, it was possible to imagine that the ability to revel in dystopian decay—which has gotten us this far after all—could sustain us through whatever fresh catastrophe we’re hurtling toward now.

The crowd reassembled along the water’s edge as choreographers/performers Symara Sarai and Kashia Kancey waded into the surf. Sarai, whose practice is devoted to—in their own words— “making space for queer Black femme anarchical play,” cultivates improvisational dance realms that allow suppressed rage, sorrow, and joy to come to the surface. Kancey’s choreographic work explores labor, love, desire, memory, and (un)reality.

As sonorous tones descended over the shore from the speakers by the dunes, Sarai and Kancey began hurtling their bodies into the wet sand, crawling out of the water, then falling back again, as if pulled by an indiscernible force. Positioned several feet apart, both knelt in the surf—backs to the open ocean—and began bowing as if in prayer, scooping up handfuls of sand, then bowing again; I couldn’t decide whether their movements had more in common with drawing or sculpture.

Rising from the water, they turned on each other, grasping at dripping hair and drenched fabric, wrestling one another to the ground, then struggling to their feet, only to be met with a frenzied tangle of limbs. Their intermingled voices rolled over the crowd with growing intensity. The audience separated, then reassembled, as Sarai and Kancey made their way—still at each other’s throats—up the beach, eventually circling a chasm in the sand with a metallic silver sheet draped over its edges.

The energy on the beach had shifted palpably by the time the crowd dispersed, straggling home to rest before the night performances or hurrying to the ferry to catch the train back to the city. The piece enacted both indestructible love and insidious violence; beguiling beauty edged with pain. The world between Sarai and Kancey refuses distant, abstract notions of utopia/dystopia, instead insisting on a fierce intimacy that, whether generative or devastating, is unwavering in its softness.